Independent Collectors

Mario von Kelterborn – Weserburg

As part of the "Young Collections" series at the Weserburg, Mario von Kelterborn presented works from Collection von Kelterborn in the exhibition "Young Collections 02".

In this interview to mark the opening of "Komm und sieh - Sammlung von Kelterborn" at the Weserburg, Christine Breyhan spoke with Mario von Kelterborn to talk about his collection and why he chooses to collect socially oriented, philosophically profound, and politically explosive works by a whole range of internationally acclaimed artists.

“Brûler le Louvre! – Burn down the Louvre!", was the Impressionists’ clarion call after the artists were denied an exhibition in the muses’ temple. Yet not only is the Louvre still standing, but it has also been joined by numerous newer museums now eager to open their doors to contemporary artists. Is the collector who grants public access to their works of art, as you have done in the exhibition “Come and See” at the Weserburg, also a kind of door opener, a go-between, an educator and art patron rolled into one?

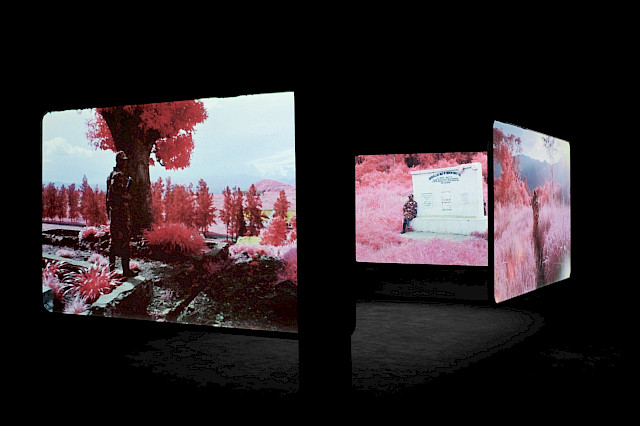

Absolutely! Art shouldn’t lie dormant at home. If we collectors are prepared to involve the public domain we can start by showing privately collected art in museums, and by complementing the collections with loaned works. I believe art should be presented in a contemporaneous manner since it addresses issues that affect us all right now. It’s part of the museums’ educational remit. Take the work “The Enclave” by Richard Mosse. The Congo is in the news just now – in fifty years time we will only be able to look back on it, whereas today we can still change things.

In spite of this development, museums struggle and reckon with political and public rebuke if they venture too far onto avant-garde terrain. “People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” says one proverb. A brickbat wrapped in Hannah Arendt’s treatise “La tradition cache” could be a bone of contention and the work by Claire Fontaine might be a missile but it is still a symbol. Is it not conceivable that in the long term, words might prove harder-hitting and more powerful projectiles than actual bricks?

Yes, that’s our basic attitude. Prior to the exhibition we had an intense discussion about this work. It could be the subject of debate particularly in Bremen since – something I didn’t know before – this is where the Hannah Arendt prize for political thinking is awarded. For me this brick should be placed at the front when the prize is awarded because it addresses precisely this issue. Think about it! Am I a stone or am I wrapped in words that weaken me as a stone? It is fairly rare to come across a work like this that consists simply of a brick, a sheet of paper and a rubber band.

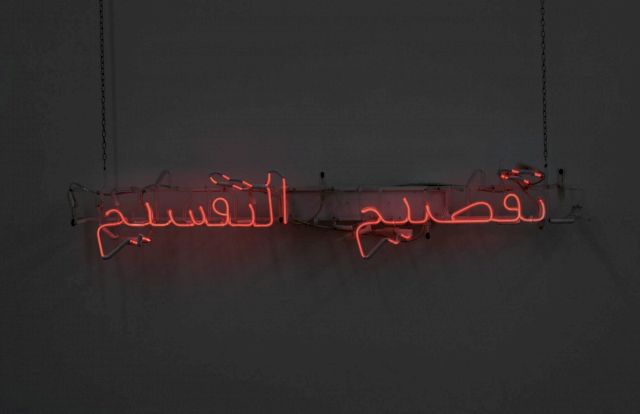

This isn’t the only work in your collection that works with words.

Indeed, we have two neon signs by Claire Fontaine in the collection: “Diviser la Division” and “Sell your Debt”. The moment you see “Sell your Debt” you are tantalized by how spectacular it is to compress economic history into just three words. I work in business and for me, in thematic terms, it’s such an intelligently conceived piece. Not unlike Thomas Locher. On view in the exhibition are two Schuco windows like the ones you get from DIY shops, that are inscribed with text. One text says: “Was mir gehört kann nicht dir gehören” (What is mine can’t be yours), which in terms of art is plainly wrong since the moment an artwork is publically shown it instantly belongs to everyone. Everyone can share the idea with others and process it for himself or herself. The other text relates to the economy: “Ware wird produziert um verkauft zu werden” (Goods are produced to be sold). Yes, obviously. But why is that obvious? People have always produced things to exchange with one another and to sell. That’s the basis of the economy: that we want things from other people.

“We are tremendously curious to see if visitors are willing to step beyond a certain comfort zone.”

Frequently enough, once art has been purchased it disappears from public view. Visitors to this exhibition bring new eyes and prompt social debate. For you, how important is audience reception?

Very much so! Discussion about a work of art and the artist already begins with the two of us. Reception already starts when we are visiting an art fair, a gallery or an exhibition where we encounter an exciting artist. Maybe then we happen to take a shine to the work and artist and begin by taking one work back home with us. And there’s a lot more gathered here in the museum. This is not about single works of art but a whole exhibition intensively addressing different ideas. We are tremendously curious to see if visitors are willing to step beyond a certain comfort zone. With that I mean, for instance, how viewers respond to Richard Mosse’s work “The Enclave” in the black-walled Otte gallery.

This is a very important work in the collection concerning the conflict in East Congo that since 1998 has cost the lives of 5.4 million people, but which has gone largely unnoticed in the rest of the world. By immersing the green landscape in psychedelic red and pink from the means of old military reconnaissance film material, Mosse succeeds in creating such arresting imagery that the conflict is given a truly tangible presence.

What are you hoping to achieve with the exhibition’s accompanying program? Informative events of this kind are something of a rarity when you visit private collections.

There is a film program. The title of the exhibition “Come and See” derives from an eponymous Russian anti-war film made in 1985 by Elem Klimov and was a very deliberate choice. Performance rights for the film were granted by the former Soviet Union exclusively to the GDR and it was back then that I first saw the film. It lasts over two hours and has images you’ll never be able to erase from your memory. That was an important moment in my youth. The film’s hero is a boy, and in the four years of the Soviet Union’s participation in World War II this kid who loses everything around him becomes a partisan and, in truth, an old broken man. The actors play this story entirely without pathos.

You present visitors with an ensemble of works that has not been seen in this form before. Does this include any work that has previously never been shown?

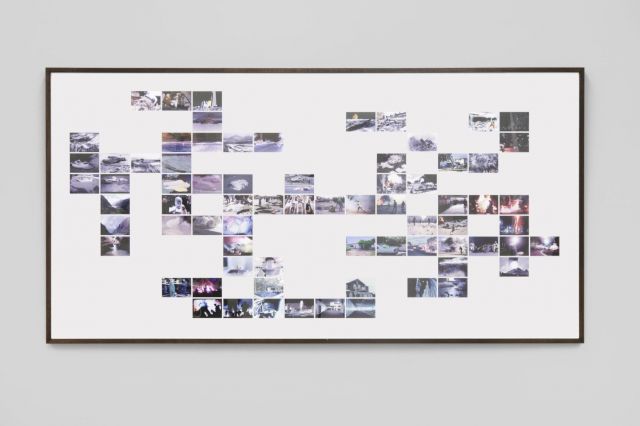

There’s one work by Björn Malhus, “You are Never Alone”, a witty, enigmatic table-football object that has never been shown in a museum before, for example. Or a large-scale work by Taryn Simon, currently the subject of international attention, called “Avatar”, a motif we also employed for the invitation card and the poster for the exhibition. Simon assembled the composite image of a generic politician from various body parts – face, nape of the neck, shoes, and so on – whereby all the different anatomical parts belong to actual political leaders, from presidential candidates in the U.S. and former foreign ministers to real dictators from all over the world. Taryn Simon has not seen this work since it was purchased so she’s delighted it was exhibited here. This, in turn, is one of the pleasures of being a collector.

Private collectors decide their own agenda. They don’t have to consider profit or listen to the views of art critics or the general public. Can this complete freedom sometimes also be an impediment?

As of yet it hasn’t been an impediment. But because there is no budgetary limit, and because this is a passion and a source of immense pleasure, you now and then can make mistakes as a collector. For one, you spend far too much of your time with art on your mind, leaving too little for family and other things. The other is that you simply spend far too much money! Suddenly a work of art comes up and you think, “that’s an absolute must!” And if you’re somehow genetically hard-wired to be a collector this “absolute must” is monstrous, because there really is no alternative. Saying that, it is also self-determined, as opposed to when a higher being tells me “you have to” or “you may”.

Can a professional adviser come in useful here?

Certainly! There are a number of serious art consultants. In Germany it is not so common but in the U.S. it is quite normal, particularly in specialist areas that you are less well versed in. What, of course, an art consultant can do to begin with is to clarify fundamental questions. Why do want to purchase art? Do you want to decorate your house? Are you keen to invest money or make a financial yield? Are you interested in intellectual questions? The consultant offers orientation in how best to operate within a prescribed budget. They can help you discover exciting new works or expand your perception and they will introduce you to a technical vocabulary – you stop talking about “lovely pictures” and refer to them as works. This can help the future collector simply feel more at ease. At the outset this is very important because collecting truly is a world of its own. I know this from a number of friends who are nervous about stepping inside a gallery. These are experienced people with both feet on the ground, but in this respect they feel very inhibited.

Walter Benjamin described this intimidation of the threshold as the magic of the threshold.

That’s what is so great about overcoming your fear of crossing the threshold, then it really is a magic world you enter into. A good adviser can indeed be useful in that.

“I believe each period calls for its own media of artistic representation because visual habits and technology are constantly changing.”

Even though there is no imperative for you to take the bigger context of art history into account, your collection does nonetheless, and in a highly topical manner. It reflects on classical, established themes – such as the self-portrait (with Clemens Krauss), seascapes (Gary Hill), images of warfare (Hu Weiyi). What makes this kind of historical reference feel so contemporary?

I believe each period calls for its own media of artistic representation because visual habits and technology are constantly changing. The focal point of our collection, video art, didn’t start until the mid-sixties. And even photography is barely 200 years old. Certain technologies could not have been adopted earlier, let alone even imagined. But video and photography do not replace painting; they just show things in a different way, with a contemporary gaze. In other words, we perceive with the eyes of today. Taking Gary Hill as an example, if I wanted to include a classical seascape in the collection I wouldn’t delve so far back into history. I’d take Hiroshi Sugimoto. He creates unbelievably calm, perfect seascapes. Gary Hill’s work, on the other hand, such as his video with the surfboard and the wave as it is breaking makes me think of tsunamis, of threat, of existential issues. What happens when the wave crashes down over me, does something remain, or nothing? The wave reminds of me of the boat people seeking to enter our world because the world where they come from no longer affords them any life. Maybe a painter 200 years ago would have rendered this subject too. But he would have employed different means and symbols that, if we hadn’t studied art history, we probably couldn’t decipher.

Gary Hill is not my generation. He was born in 1951. He’s a generation earlier – but this can be made up for when someone, as he does, retains a fresh, bold mind, as is the case with a lot of outstanding artists.

Is Clemens Krauss your generation?

Krauss was born in 1979, so he’s about 10 years younger than me.

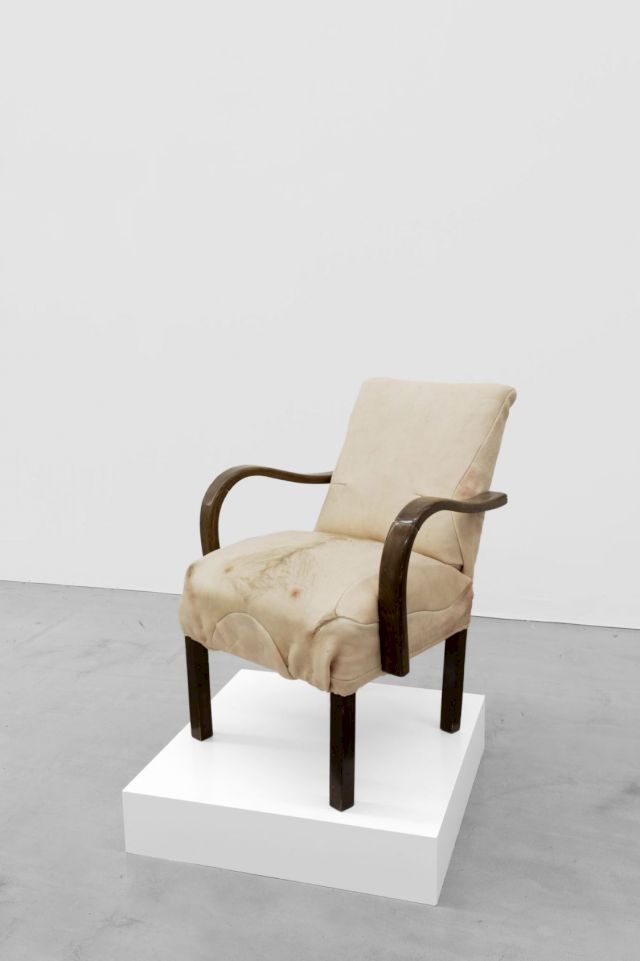

His self-portrait is quite special.

Very special. I think his self-portrait would have been ruled inadmissible for about 90% of the time since art has been shown. It’s all right for a museum for contemporary art to show this. The work will certainly have a provocative effect, if only because our perception of disgusting, naked skin can also make it feel offensive.

Yet on the other hand it is not our intention to brutally shake people out of their complacency. For me personally this work is more subtle – it addresses perceptual habits and connotations from a German perspective. When skin comes into play we are all reminded of experience familiar to us from history, from World War II.

We spent quite a while debating whether we can actually own a work like this. It is striking how the piece leaves no one cold. As Clemens Krauss has also said, the work is about inner conflict. If one were trying to title the exhibition with a single word it wouldn’t be war but conflict, both in the smaller interpersonal sense and the broader context as between powerful states.

It reminds me of the saying “to get under someone’s skin”.

Or “ to feel comfortable in your skin” – that is what the armchair stands for that he got from his granny. He implanted the hair with such remarkable precision. In one exhibition he had a work consisting of a human skin spread out on the ground, like a snake’s or as if a person had just slipped out of his skin. I was very tempted at the time but I arrived too late. It was easier to find access to it because the image was easier. But the more you think about the “armchair” the more it becomes unsettling, and this gets even more intense through all the associations he is playing with. In the other work the skin was simply cast off and left on the ground. Here he has taken the discarded skin and explicitly processed it.

What about the insect-like “Keep Crawling”?

Oh yes, for me “Keep Crawling” is particularly intense. But I’ve got a work by Björn Melhus too that is about war, images, TV, sound. He did a piece about returning war combatants called “I’m not the Enemy” for which he was also awarded a short film prize (the Deutscher Kurzfilmpreis 2011 in Gold, in animation/experimental film). It’s about traumatised soldiers returning from any war whatever and what they personally experienced there.

With “Keep Crawling” similar things came to mind: they are soldiers and we barely notice them. These small, almost naked toy soldiers crawl across a road junction in Shanghai and at some point cars just run them over. Initially the cars still swerve to avoid them, someone then steals one of the figures, but soon they all just drive over them. That made me wonder about how we deal with certain problems. We don’t take up arms to defend our basic values. So how do we treat people who do precisely that? Do we treat people properly who had to expose themselves to very particular, massive effects on their psyche? In the video the figures are wearing pink briefs. Is that really necessary? Weiyi is a young Chinese artist (born in 1990) who makes very conscious choices. We know that China has an enormous problem with homosexuality. Maybe that’s why he had his men wearing this underwear. The soldier is strong, he carries a weapon and he is wearing women’s panties. I am very keen to follow whatever else this young Chinese artist does next.

Doing this kind of research while you collect is great and as the web of information available through galleries keeps growing, we can see whether we want to add newly created artworks to the collection.

Does the collection reflect the current “zeitgeist” or more your own personal profile as a collector?

I think the two aspects are connected. For us it is quite clear, and I’m sure that any psychologist going through the collection would probably say, “I know who you are!”. But we are living in the present world and we engage with it very intensely. It’s a very personal collection – but that is always true when you personally go about collecting art. Its tendency towards conflict is probably the result of my East-West background. So, yes, the collection is very much in the spirit of the times because it’s made up largely of recent works that deal with current themes.

“I want to build a collection looking to be intelligent and thematically outstanding. Not outstanding in the sense of price and market value, but a collection that makes a clear statement while still being open enough to accommodate ideas and issues.”

Talking of which, do our times have a spirit? Do you try and track it down?

That’s a good point. I don’t know whether one has the right to talk so critically but – since you mentioned it before – the reason why the museum scene has such difficulties is because the people who hand out the money, the politicians, don’t always grasp that culture is an elementary factor of human existence, maybe coming directly after the need for basic health care. And if I stop pushing the state’s educational responsibility towards culture and also start cutting the money it receives I’ll just end up cultivating mindless automatons.

Let’s turn to the spirit of the Renaissance. The Medicis, who commissioned contemporary artists to produce work, discovered and patronized, among others, Michelangelo. That strained relations with the pope who also made demands on the artist’s labor and ideas. Are there jealousies of this kind amongst the collectors of today?

Not that we’ve noticed yet. Maybe that happens at the level of globally active major collectors who muscle in with assets of billions, who say “I absolutely have to have that big poodle piece by Jeff Koons so you can’t have it!” When it comes to trophy art, that’s true. But when you then look at our collection you’ll realize we have a lot of works that were produced as editions. A video work is seldom a unique work, as is virtually the case for photography too. As it happens, with the collection we are often the first, i.e. we were the first movers in regard to a certain artwork, although it is not always possible to buy the first edition of a work. By the time the third buyer comes along things are easier as there is less risk. Anyway, our collection is very independent of the art market. Which new “stars” are being praised to the heavens by the market is at most only of peripheral interest to us.

The sheer range of your objects of desire is as varied as your motives for collecting. So, to put it in banal terms, why does it have to be art and why in particular “Gangster Backstage” by Teboho Edkins?

I am a passionate collector and started out with postage stamps. But art is much closer to people. For us art is important, it completely animates us. And then you encounter a work like the one by Teboho Edkins – his really has a fresh approach and was shown in a gallery for the first time just the other year. His films are now shown at festivals and in 2014 he won first prize at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, the oldest short film festival in the world. But he didn’t make his leap into the art world until a couple of years ago when he met a Frankfurt gallerist who told him, this is video art; which is how his work came to be shown in a gallery. I only needed to see one-and-a-half minutes of his altogether 35-minute film to know this was something that would be an amazing addition to the collection. Finding it was like finding the missing piece from a jigsaw puzzle, it was a feeling you can hardly describe. That’s what it must feel like for a scientist when a final additional idea shoots through his brain. “Gangster Backstage” is a conceptual work, which also includes ten portraits of gangster actors and the advertisement Teboho placed when he was casting for suitable gangsters for his film. These are moments when I tell myself how lucky I am to be able to collect.

You insist on specific forms of presentation. For Richard Mosse the large gabled gallery was lined in black. Why?

It’s what the artists prescribe. Nowadays, if you buy sound and video installations you also get a certificate concerning the ownership and performance rights and how the work has to be presented. That’s important because the artist previously works out a method for how his ideas would be best conveyed. Mosse also decided that six large screens should not overlap in terms of stray light, nor should there be any reflections on the walls. Besides, the work has very intense color: white walls would diminish its effect. In addition, with the black room he has created a situation of vulnerability and deprived orientation. At times all six screens are in use, occasionally it’s just two or three, and there’s even a moment when not a single one is playing. Suddenly bombs go off. That might not exactly transpose us into a war situation, because that would always be more intense, but it does take us very far way away into an unpleasant setting. With the sound it is similar. The lateral surfaces and the ceiling have been lined with brush cotton Molton fabric that will absorb sound, preventing the soundtracks from six different acoustic sources from overlapping, and also to avoid sound reflecting back from the walls. These specifications have to be complied with, they are an integral part of the work.

Does your collection have an immutably fixed core or is it in a constant process of change and renewal?

Not so much renewal – that’s like claiming we give away a lot of what we have since we don’t deal in art. There is undoubtedly a very important nucleus: we concentrate strongly on video art, with Gary Hill in particular as a focal point. Our first work by him dates back to 1973. So we can follow forty years of an artist’s development within video history, in technological and thematic terms. Early on, there were works in which he used transistor technology to create lighting effects. Then he shifted towards dramatic narrative, i.e. he made films as it were, right up to the work on show here, “Isolation Tank”: this seascape was entirely computer-generated, is pure fiction.

Hill truly does belong to the solid core of our collection. Round about this there are occasions when we will exchange works, but the overall character of the collection rarely changes.

Tom Sawyer’s collection fit almost inside his trouser pocket. Were you already a collector as a child, with a shoebox under the bed perhaps?

Yes, when I was young it really was postage stamps. I was interested in philately: it’s an early sign that you want to compile things and engage with what you have collected. And as with art, it is much easier for me to engage with something when I possess it than just by looking at it. Philately can be a perfect mirror of history. For a long time mail was the number one means of communication. But just collecting telegraphy, letters, postcards and stamps is not enough. It has a postmark on it, so you can see where the stamp was used; then you see it was registered mail, an insured letter, so it had more stamps on it and there is a lot more written by hand on it too. During the Great Inflation you see postage cost ten pfennigs, and then within four years sending a letter cost twenty billion marks. With wartime mail, a letter became a philatelic and historical document. There is a close analogy to art here. Philately fosters a strong awareness for history; art, I believe, creates awareness for what is happening around us now and what will be history tomorrow.

Do the passionate collector and the rationally planning businessman sometimes get in each other’s way?

For me it’s more a benefit, especially as I want to build a collection looking to be intelligent and thematically outstanding. Not outstanding in the sense of price and market value, but a collection that makes a clear statement while still being open enough to accommodate ideas and issues. After all, art does not work by putting the finger directly on the wound. But there are questions we should be thinking about. It is not pure documentation. Art that is too explicit will never find its way into our collection. I believe that in my case, the collector in me is well served by the businessman’s head. Here and there, if I’m excited by a particular work the latter will perhaps remind me, OK, go ahead and buy it. But if you do you might be depriving yourself of the money you’d need for another work that might be more important for the collection. Nonetheless, we occasionally do that. For instance we have a photo by Jürgen Schadeberg, the famous shot he took of Nelson Mandela in his cell in 1994. Mandela returned to the cell again, stood at the window and looked out. In my opinion an icon of photography, also an icon of humane thinking. But this work doesn’t fit into the collection. It is not a work of photographic art, it’s a photo. The pleasure I get from this work is simply seeing the gentleness and the pride with which this still unbroken man looks out. The photo was approved by both heads, the collector and the businessman. It’s hanging in my home and when the children ask me who that is I explain who Mandela was.

All in all, it is more of a benefit to the quality of the collection not solely to be driven by passion. Maybe it is a legacy from philately to understand that real collecting is about engaging with things, about research, maybe with the help of literature. The businessman lends a hand with this, maybe because he is capable of thinking more strategically than passion.

Is there any one artwork to which you are particularly attached?

There are two levels, and one of them is changing. Currently my heart is strongly attached to “Gangster Backstage” and “The Enclave” by Richard Mosse, because they are both works you simply cannot ignore. This opinion might change in the future but we’ll have to see. When I weigh up which work I would keep if I were forced to give up everything else then it would have to be “Pop Pop Pop”, the AK-47 by Stuart Bird. AK-47 is the technical term for a Kalashnikov and behind the image is a saying from Africa: “Nothing has changed the image of our continent more than the Kalashnikov”. It’s what people say there and this is represented in a relief-like work. Utterly impressive, for me monolithic, not at all valuable, but immensely important.

I am also attached to the two windows by Thomas Locher that have such incredible truths written on them that I’d simply have to keep them.

The window is a symbol. A picture on a wall used to be called a window, a spiritual opening onto the world.

Locher is an extremely intelligent person. The bold text dominating the foreground is spiked with small-type sub-textual commentary that probably only a linguist can really make sense of. It’s not enough simply to have a command of grammar. And it certainly wasn’t by accident that he chose a window that can be opened. He could just as easily have taken a picture frame. No one else will get these works!

“When I weigh up which work I would keep if I were forced to give up everything else then it would have to be “Pop Pop Pop”, the AK-47 by Stuart Bird.”

Collector by profession: is it not really a full-time job?

You should be really asking my wife that … Indeed. Especially now in this situation it is not only time but also mind-consuming. My brain is buzzing non-stop and right now predominantly in this direction.

Your choice of works on display in the Weserburg has a highly charged political and sociological focus. Could you also imagine your wife defining the thematic leitmotif of the next large exhibition?

It’s an intriguing idea, and I could certainly see her doing that. I think the result would be a very impressive exhibition. It would show that the collection is more a reflection of people than of zeitgeist. If it were my wife selecting works from the collection it is logical that she would quickly have her own narrative in mind. Of course, you always choose your personal favorites but they are not your favorites by chance. So the outcome would be something highly individual.

The idea of my wife defining the thematic focus is certainly a realistic one. Here you are getting to see only one part of the collection, but it is very powerful in the other direction too. We have a lot of corporeal works, a lot that is representational in which human identity plays a central role, even in videos. Here we’ve exhibited two sculptures by Mariana Vassileva – but we also have twenty terrific videos by her, her complete video oeuvre to date, concerning forms of human behavior and truths. Even though we already once filled an entire museum with these videos – it was fantastic – none of them would have been suitable for the Weserburg exhibition.

Is it perhaps like the image of a grain that gradually shoots without anyone making demands on timing or content?

Of course it has to be doable. Now that the collection has been shown once, maybe another museum will say that they can present it as well. It’s exactly the same with individual artists. Maybe opportunities will arise to bring about this idea. After all, my wife is as intensely engaged with art and knows the works as much as I do. She simply has different frames of reference.