Independent Collectors

dslcollection x Photo London

The dslcollection is a supporter of Photo London, presenting its virtual museum with the fair, here with an interview and artworks on collecting photography.

DSL Magazine Issue 12 x Photo London

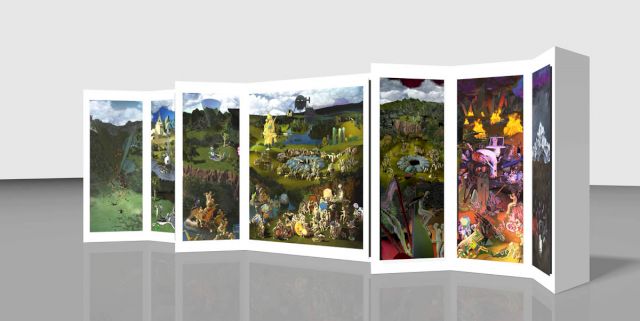

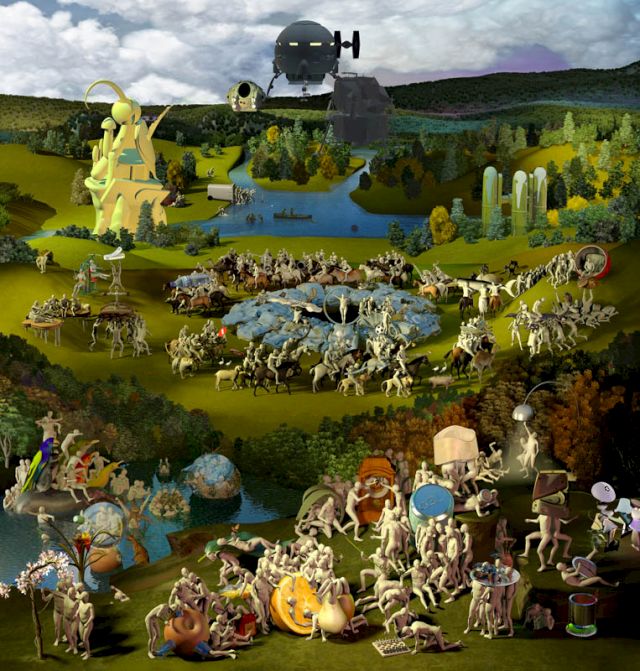

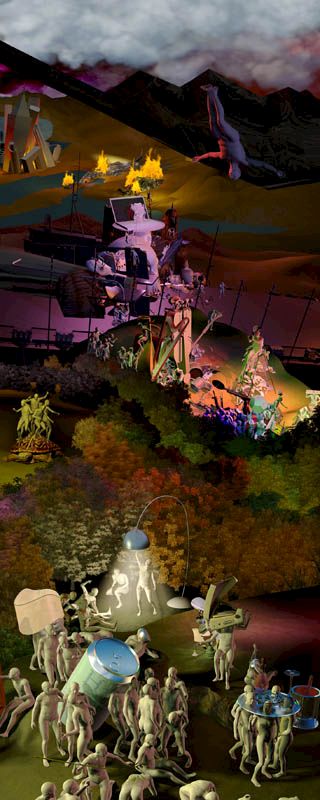

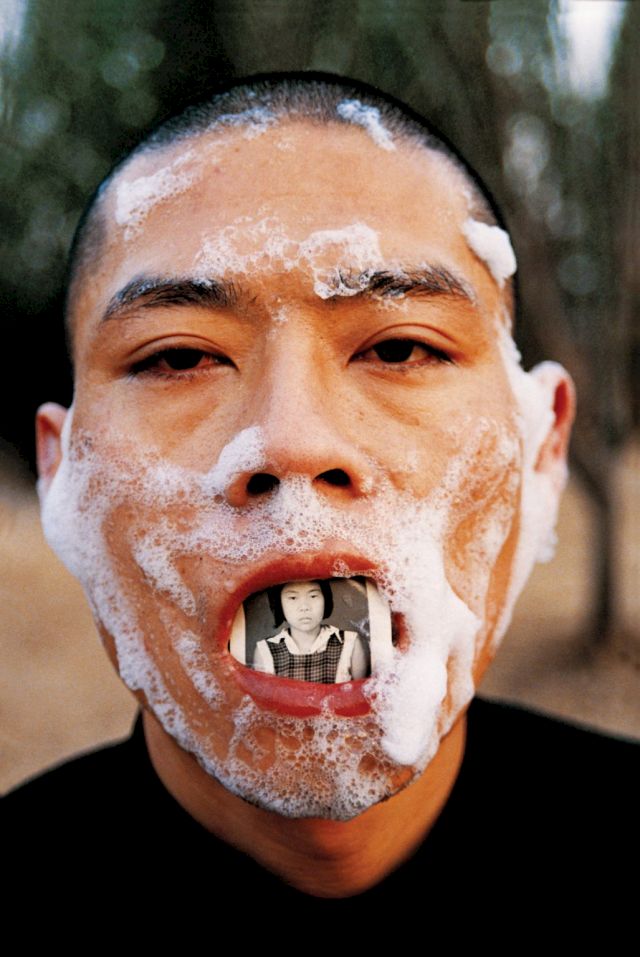

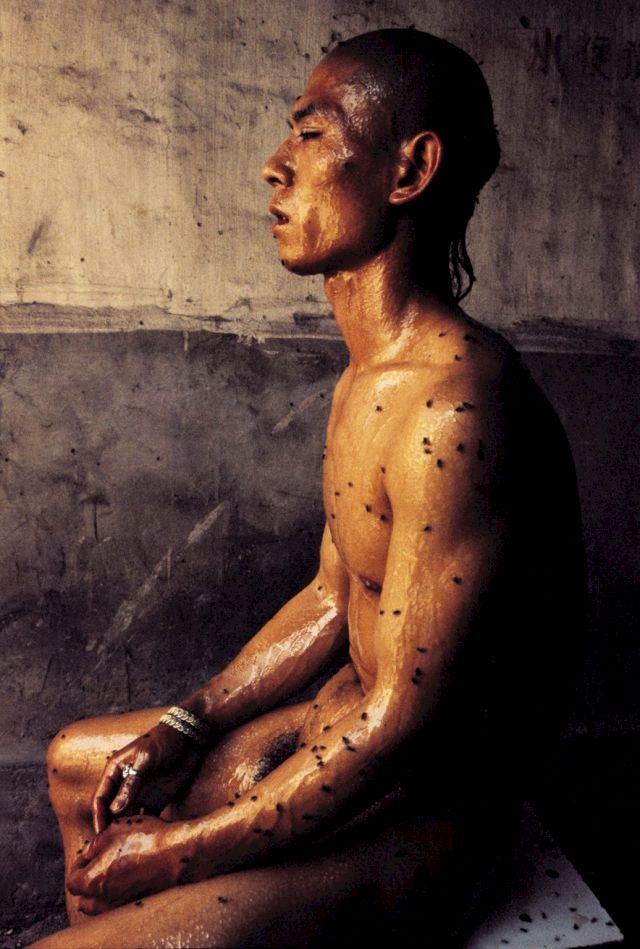

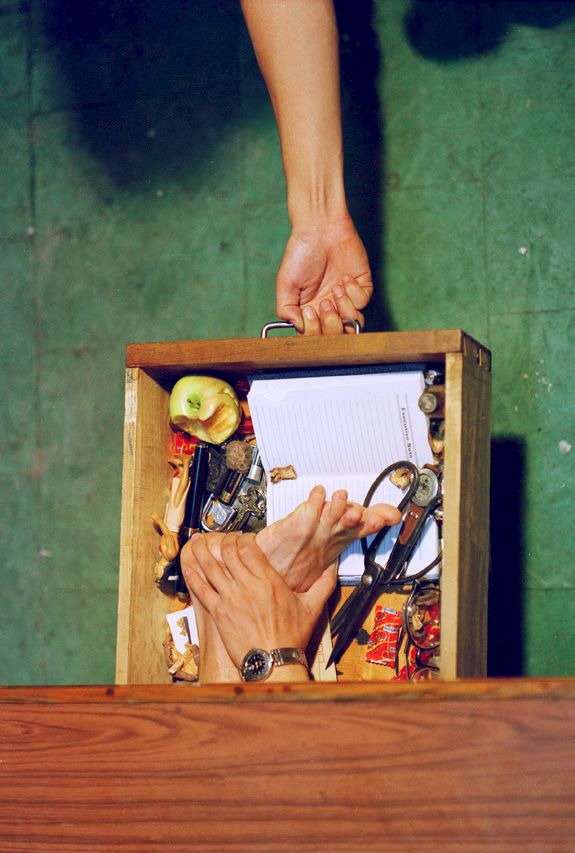

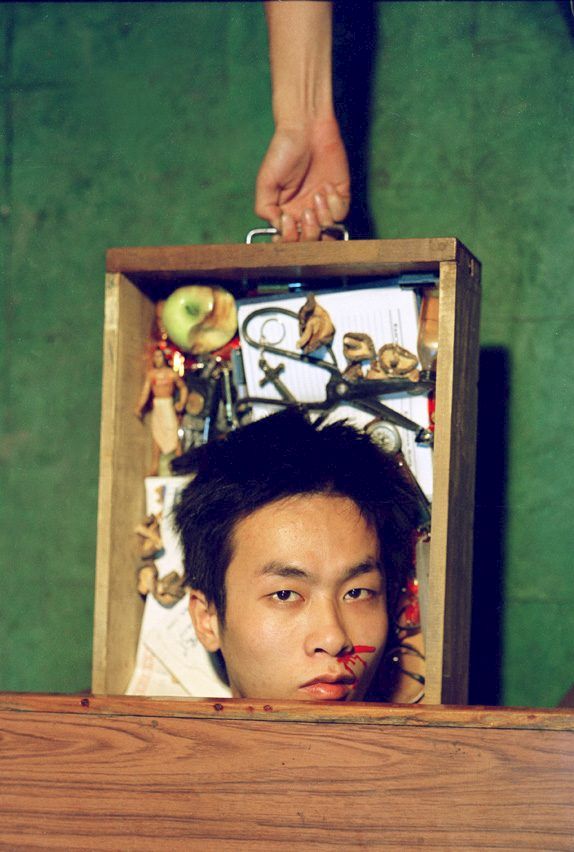

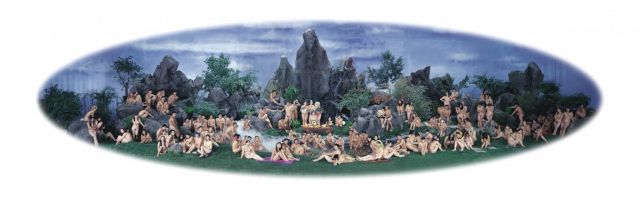

Founded in 2005 by Paris-based collectors, Sylvain and Dominique Levy, dslcollection features over 350 works by 250 artists, from the first generation of contemporary artists (those who were already active around the Chinese Avant-Garde Exhibition in 1989) to the new generation of emerging artists, many of whom are relatively unknown in the West. The dslcollection encompasses works from across all media, including painting, sculpture, photography, videos, installation, and digital art. Some of the biggest names in Chinese contemporary photography are in the collection, including Rong Rong, Zhang Huan, Miao Xiaochun, Sheng Qi, Shi Guorui, Wang Qingsong, Zheng Guogu, and Zhang Dali.

Having presented some of the collection’s works and the virtual museum at previous editions of Photo London (2017 and 2018), dslcollection is also pleased to share details of Photo London Digital Fair 2020, which was open to the public from 7th to 18th October, 2020.

In this feature, we share the DSL Magazine #12 interview with collector Sylvain Levy, as well as artwork images from the dslcollection.

A lot of artists in the collection seem to work with a diverse range of media, rather than just photography alone. How do you choose which works to collect from these artists?

Sylvain Levy: Whenever possible, we try to meet the artists in person and get to know them first. After we do our “homework”, we decide which works to collect. Since many contemporary Chinese artists do work across different media, we often collect in a similar way. For example, Gu Dexin, Zhang Huan, and Zheng Guogu are three artists who really excel in all types of media – paintings, photography, videos, and installations. As a result, we have collected different works from these artists to fully illustrate their creativity.

What are your thoughts regarding photography as a medium for Chinese contemporary art?

I think it’s extremely important as a medium especially from a historical perspective. Photography is the key to documenting the evolution of Chinese contemporary art and has led to numerous different artistic developments since the 1980s.

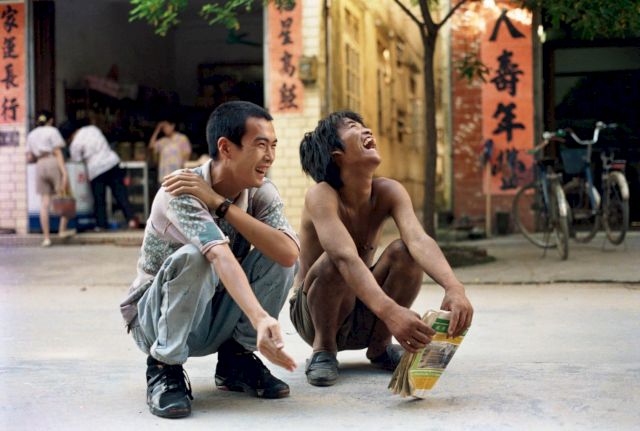

In the beginning of what we now call “Chinese contemporary art”, there was a lot of performances, and photography became a way of capturing these performances. These photographs continue to be invaluable records of a critical moment in the development of avant-garde Chinese art.

In the West, photojournalism has been around for a long time as a way to record historical events and to convey the chaos and aftermath of those events. In China, the significance of photography is threefold – historical, artistic, and autobiographical.

One of the key proponents of contemporary photography in China is Rong Rong, who is in turn synonymous with Beijing’s East Village. A group of then-struggling artists and musicians settled in the East Village between 1992 and 1994, and it soon became a hot spot for young experimental artists from around the country. In the beginning, Rong Rong focused his camera on the performances of his fellow artist friends (including Zhang Huan), some of which were carefully choreographed. By late 1993, a new type of “performance photography” had emerged; rather than simply documenting a planned performance, these photographs were more spontaneous and became part of the performances themselves. These photographs were especially important in giving an identity and proper recognition to these young, experimental artists.

What are the key differences that you’ve noticed between Chinese contemporary photography artists and their Western counterparts?

Speaking very personally, I think that it comes down to aesthetics. Western photography focuses more on the visual impact, while Chinese photography is more about illustrating actions and performances. Of course, there are plenty of artists in China who are very westernised in their use of the medium. For example, Yang Fudong is all about aesthetics, but also with Chinese inspiration.

Do you think the new generation of artists in China is still interested in traditional photography?

From my experience, the new generation of artists is much more experimental, and they continue to work across different media. While the previous generation of artists (i.e. 1980s-1990s) has focused on combining more classical media such as paintings and installations, the younger generation is now experimenting with videos and digital art. Of course, video and digital art both originated from photography. A good example of one such artist is Hu Weiyi.

Fashion photography is a well-established collecting category in the West. Do you see the same in China?

Not from personal experience. I think the value given to fashion photography is very different in China, simply because of the vast proliferation of images. Think about billboards, advertisements, magazines, and various social media. Images of luxury brands can be found everywhere. Almost everyone, regardless of socio-economic background, in the major cities of China has a mobile phone. Taking photos and videos is almost a national pastime. It’s very difficult to define which work is collectible and which is not.

From your experience, do you think the mainland Chinese collectors are interested in collecting photography?

Yes, to an extent. Like all collectors from around the world, they often include some photography in their collections. The main advantage of collecting photography is the lower entry price point. Not only are photographs less expensive, they are also much easier to exhibit than videos. I also think that a large part of the newer, younger collectors look at photography as a way to decorate their homes. In a way, Chinese collectors’ behaviour is probably not too different from those in the West.

You mentioned meeting a lot of the artists in the collection. Could you tell us any interesting stories?

Dominique and I have a policy to meet as many of our artists as possible. There are so many different and interesting stories, but the ones that really stand out would include Wang Qingsong (for his personality and incredible creative process), Zhang Huan (for his personal account of Beijing East Village), and Zheng Guogu (for his stories about the Big Tail Elephant Group and River Delta). To be honest, every artist in the collection has a fascinating story, and all of them become part of our collection’s story. That’s one key reason for the collection; it’s a journey and an adventure.

Finally, any advice on how to collect photography in general?

I think that collecting photography is the same as collecting any other medium. There has to be meaning to collecting; it could be as simple as “I like the work”, or it adds something to the collection. I’ve always believed that “art is a mirror of society”, and photography reflects that. There is something we do that might differ from other collectors. Whenever we collect a photograph, we always ask the artist for two editions. One that is signed by the artist, which goes into the collection; the other is unsigned and can be loaned for exhibitions. As you know, photography is a very fragile medium. To avoid damage from strong lighting or atmospheric changes, we always try to collect two versions.