Independent Collectors

Remembering Mwene Mutapa – Exotic Mapping of a Collection

The Brussels-based contemporary art collection marked by a non-Western focus.

Allegedly, it was this Zimbabwean prince that conquered these lands, located on the fringes of the Indian Ocean, stretching between the Limpopo in the South through the Zambezi in the North, occupying highlands more than 1000 meters high. He called himself the Mwene Mutapa (“Lord of the Mines”).

The trade of ivory, copper and gold with the Arabs, the Hindus and the Indonesians made the region even wealthier than it was several centuries before, as Ibn Battuta reported in 1331 upon visiting the ports of Kilwa and Sofala, Arab merchant towns that later became Portuguese trading posts. For a long time – until the downfall of the kingdom – the Mwene Mutapa and its mines were protected from the greed of all kinds by its hostile lowlands and arduous fluvial access. The country nevertheless raised the curiosity of explorers, who believed that the ruins mentioned by indigenous people were part of the mythical land of Ophir, the source of King Solomon’s gold and riches. Archaeological digs also revealed the presence – besides copper, golden and ivory African objects – of a number of imported utensils and artworks (Indian pearls, fragments of Chinese porcelain, Persian earthenware and Syrian glassware) as well as silk and cotton fabric from India and Eastern Asia.

Fast forward to today and the contemporary art market has its own classic destination and world-famous meeting places, from annual art fairs to seasonal auctions and regular events such as the Venice Biennial, Documenta Kassel, Skulptur Project Munster, and so on. It is in these places that the production of a minority of Western artists is sold for astronomical amounts of money to a fringe of Western buyers that compete with each other within a reassuring bubble. However, new dynamics have recently received attention, and revealed emerging scenes, with Brazil and China at the forefront – a phenomenon that had repercussions on their neighboring countries: Mexico, Argentina and Colombia on the one hand, Japan, Indonesia, India, and Singapore, as well as, of course, the Middle-East and Northern Africa.

The creation and development of commercial and cultural initiatives in these regions have redefined the migratory routes of an endangered species: the collector. While those interested in emerging scenes mainly buy works by local artists, other collectors set to explore new territories, seeking to discover, appreciate and bring back the specimens that will complete their treasures and attract the curiosity of their peers. For a long time, art works from these countries would only be attached to ethnographic collections as natural, regional productions. But then came the desire to study these pieces for the sake of their particular plastic language, to appreciate and identify their formal language. How do we look at the current productions from these territories? Who creates them? What are their aesthetics? What lessons do they teach us? How do they animate our and the globetrotting collectors’ enthusiasm? Is it a sinister echo of our colonial past, or an attempt at connecting with the “Other”? In the words of Victor Segalen, exoticism is everything which is other. Taking pleasure from it means learning how to savor the diverse.

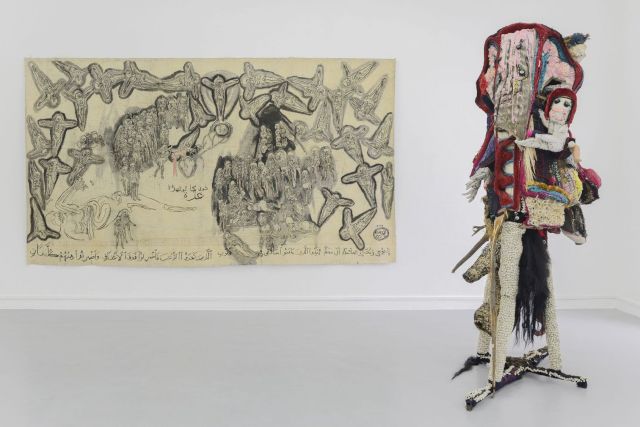

This research will focus on artworks from the Servais Family Collection. Over the last twenty years, former investment banker and collector Alain Servais has gathered a collection of hundreds of contemporary artworks kept in a three-story loft in Brussels. Each year, he travels around the world, seeking new horizons. His collection is marked by a non-Western focus, as a reaction to the evolution of the world. According to Servais, the West is gradually getting stuck in its own comfort while ignoring the rest of the world. “Western art is currently an art of comfort, it has become a luxury product, devoid of meaning and of real objectives. Once, a relation living in São Paulo told me that the Brazilian art was so powerful because it represented the apex of the country’s internal tensions. I believe that the most powerful art results from tensions. In the West, we tried to artificially suppress them.”

In this online exhibition from the Servais Family Collection we present the three installments of the exhibition “Souvenir de Mwene Mutapa – Cartographie exotique d’une collection” titled “L’île aux Lignes”, “L’île de la Mémoire”, and “L’île aux Mythes” curated by Nicolas de Ribou and was shown at La Box, Bourges from January 5th to April 15th 2017.

Text by Nicolas de Ribou (translated by Jean-François Caro)