Independent Collectors

Christian Kaspar Schwarm “Young Collections”

Inside the constantly growing and unconventional collection of the IC co-founder.

In the fourth part of the “Young Collections” exhibition series at the Weserburg, Bremen, Christine Breyhan sat down with Berlin-based collector and Independent Collectors co-founder, Christian Kaspar Schwarm, to discuss the works presented in “The Vague Space”.

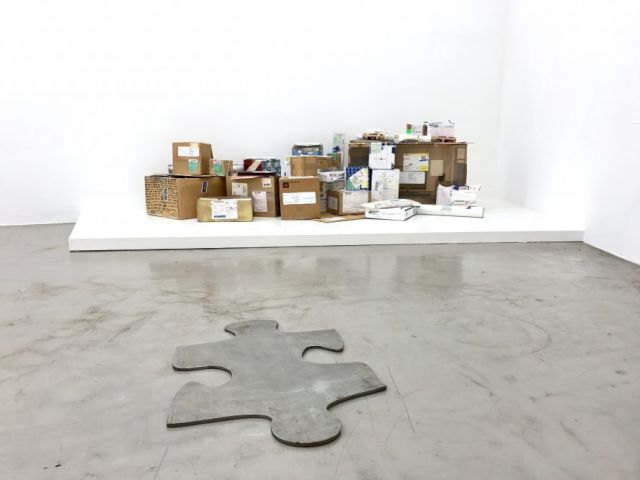

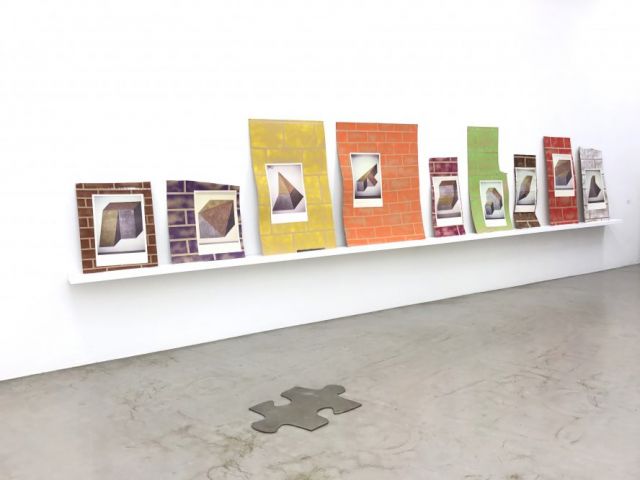

After building his collection over the last decade, Schwarm realised the first solo presentation of the collection in the exhibition “The Vague Space” at the Weserburg, which was comprised of installations, video works, and pieces with high political aspirations. A multi-dimensional collection, without any specific focus on a medium, “The Vague Space” featured artists such as Nina Canell, Slavs and Tatars, Michael E. Smith, David Horvitz, Karin Sander, and Jonathan Monk to name a few. Here, Christian Kaspar Schwarm speaks with Christine Breyhan to talk about the foundations of the collection and why now is the crucial time for a shift in the perception of collecting art.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

“Every creature of the world is a book and painting and mirror for us, as it were.” In “The Name Of The Rose”, Umberto Eco teaches how “to read the signs with which the world speaks to us like a large book.” Christian Kaspar Schwarm, the presentation at the Weserburg issues an invitation to learn to read the signs in works of art and offers a temptation to see the collector mirrored in his collection. What is waiting there for the viewers?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

I’m quite familiar with the language of signs about which Umberto Eco is speaking there. And one thing I like about your question is the comparison with a book that we have to open in order to read something inside it. It’s quite exciting to also think of this exhibition as that sort of book. But it would be quite a heterogeneous book – with entirely different chapters arranged in a non-linear succession and interspersed with pictures that have somehow ended up at an appropriate place between the pages. So you wouldn’t feel obliged to read this book from the first to the last page but could discover it by a combination of thumbing through the pages and pausing here and there. I’m thinking of Alexander Kluge: he does wonderful books on a wide range of topics and tells countless stories, some of them fictitious, some with a historical background. Wherever you open them up, you immediately enter a new micro-world.

This is how I would like to view the exhibition at the Weserburg and my collection in general: each individual work of art serves simultaneously as a window onto the entire oeuvre of the respective artist. A work has its character as a solitary specimen; but at the same time it also becomes a representative of the artist’s overall production; because as a matter of principle, I focus intently on the creative output of artists who interest me. So from the standpoint of the individual work, I also always view the total oeuvre.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

The title of the exhibition consists of two terms whose complexity expresses the connection between images and texts. How did “The Vague Space” arise?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

I first encountered the notion of “The Vague Space” in an essay by three artists with whom I am friends and who operate along the interface between art and the natural sciences. For me, that was one of those rare moments when one experiences something like a minor epiphany: I immediately recognized that these three words constitute a pair of brackets between which lies all the art that fascinates me. After I had read the aforementioned article by Jannis Hülsen, Stefan Schwabe and Clemens Winkler, I immediately telephoned and asked whether I could borrow the title for our exhibition. “The Vague Space” also referred to the interactive workshop that the artists presented on the Saturday after the opening – so that the authors and the quotation once again came together.

For me, however, the exhibition title describes not only an interconnection between pictures and texts, but also a far more general multi-dimensionality of young art. I always envision that as a multiplicity of levels that touch, cut, intersect and overlap each other at various points in a three-dimensional space. What I particularly love about the works in my collection is their many layers, their ensuing indefinability and the impossibility of reducing them to merely one or two interpretations. Often a handful or even a dozen different levels coincide in them, and years later I discover even more. Most of the time, really good art actually conveys much more than the artist was aware of while creating it.

With Lukas Stopczynski, we invited a further protagonist to the Weserburg whose work brought vagueness and uncertainty into the exhibition as live components. He arrived a little less than a week before the opening, irrupted into the museum with countless objects and materials, and at that point didn’t yet know himself what would happen. Hats off to the museum for its own audacity, especially because with Lukas’ oeuvre it wasn’t even the case of an “established position.”

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

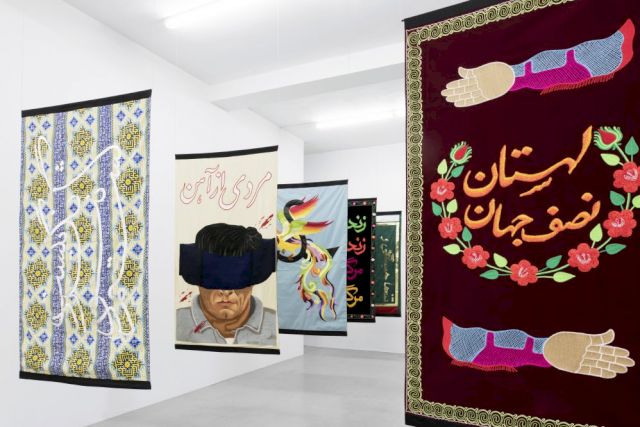

In an era in when once again there is talk of the decline of the West, what role is played by political works – for example, the textile banner “Friendship of Nations” or “Triangulation” by Slavs and Tartars?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

I myself learned quite a lot from the work by Slavs and Tartars – about historical developments in quite diverse geographical spaces, about political and religious conflicts, about understanding and non-understanding between peoples and cultures, about the mutability and instability of language … I could go on and on with this list. The artists’ collective Slavs and Tatars focus on the three great narratives of the twentieth century: on Capitalism, on Communism and on Islam – and on the respective interrelationships between these dimensions. The members often take up special aspects of history and transfer them into works of art. As a “child of the West” – I was born in 1972 – I experienced during my youth the Cold War, the NATO double-track decision in the 1980s and the ensuing peace movement. At the latest with the fall of the Wall, political Islam took over serving as the image of the enemy of the West; in retrospect, almost in the form of a changing of the guard with respect to Communism, or a handing over of the baton.

Only through Slavs and Tatars did I become aware of the relative narrowness of my Western orientation. If you look from one vertex of a triangle at the two other vertices, it will never be possible to see the entire geometric shape – and thereby to recognize it as a triangle. For example, I didn’t know anything about the former relations between Communism and Islam. The cover picture of the exhibition poster shows a work directly concerned with this axis: it presents the aforementioned concrete block upon which may be read in various languages the words “Not,” “Moscow” and “Mecca.” The work thereby refers to a political doctrine of the USSR, which, at a certain point in time, admonished its Islamic republics: “To Moscow, not Mecca.” The work by Slavs and Tatars, however, elects not to choose between the one narrative and the other. When there is talk of the decline of the West, then from all sides and on almost every occasion we are presented with oversimplifications and accordingly one-dimensional arguments. Art – especially young political art – can, however, at least open our eyes to this, because someone who has once recognized this fact will not soon forget the insight.

For me, there is nothing abstract about art and collecting art. I live with art each day; it is a sort of spiritual nourishment for me.

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

Art has no need of justification. The collector is not required to explain neither his selection of artworks nor his motivation. But isn’t it the case that the perception of a private collection in the context of a museum is also surprising, perhaps even contradictory for the collector as well?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

The surprising and the contradictory: that’s right on target in my case. I indeed have a feeling as if my life were suddenly being placed on exhibit here at the Weserburg. Of course, not in a form where private experiences play a role – but certainly one where it is a matter of extremely personal ideas, values and turning points. For me, there is nothing abstract about art and collecting art. I live with art each day; it is a sort of spiritual nourishment for me. This occurs throughout my apartment, all the way to the bedroom. Putting my collection on display here is not less personal – on the contrary. One of my “predecessors” in the series of Young Collections that are presented at the Weserburg described this feeling on the evening of the exhibition opening as a “total striptease of the soul.” But we consoled ourselves with the thought that none of the other guests know about this subjective sentiment; for the most part, they don’t have any idea how profound a perspective this sort of collection opens onto the personality of the collector.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

The work “Word Search” by Karin Sander radiates something incidental and frugal. It has a fortuitous quality, as if framed by accident.

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

Karin Sander went through New York and searched for as many different native speakers as possible. Then she asked these persons to write down the word that was most important to them. This was often a challenge, also because Karin Sander didn’t want to make a notepad or pen available. So the respondents reached for whatever was at hand and wrote their most important words on slips of paper, napkins and beer coasters. The actual work ultimately came to consist of 250 facsimiles of these original documents, only nine of which are to be found in my collection. What is more, each individual document differs with regard to language and handwriting. The word “chickpea,” for example, seems to us to be more than a drawing.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

The videos of Guan Xiao and Mario Pfeifer get lots of attention. What place do they occupy in the collection?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

Strangely enough, I never intended to integrate video works into the collection. There are collectors who specialize with great passion on a certain epoch, genre or technique. Nothing could be more foreign from my point of view, because what counts above all for me are such things as the idea, the concept, the contents, the perspectives. But when video works suddenly touch me so emotionally and even shock me in a positive sense, such as was the case with those two works, then it would be equally false to refrain from collecting them because of a purely formal, medium-related criterion. I’m only really free when I neither specialize in something nor negate anything. Both standpoints would limit me in equal measure.

I discovered the work by Mario Pfeifer at a gallery together with a female acquaintance. After we had viewed it several times in succession, we stood before the gallery owner and were apparently trembling – he continues even today to swear to that perception, and I have no reason not to believe him. We were so moved by these interwoven and cleverly overlaid perspectives, which were literally incomprehensible to us, that we had no choice but to purchase the work together. And precisely because we are not romantic partners, this in turn opened a new dimension: the work is now a shared object that will accompany our friendship for a lifetime and will remind us of the overwhelming power of art.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

In 1863 Baudelaire stated: “The pleasure offered to us by a depiction of the present arises not only from the beauty which it may possess, but also from its specific contemporary character.” Isn’t it nothing other than this disturbing, provocative contemporary character that maintains dynamic tension and stimulates an encounter in the respective era?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

On the one hand, that sounds so up-to-date; on the other hand, it seems contradictory that already more than 150 years ago, Baudelaire said something about the present that possesses such timeless validity. I wasn’t familiar with that quotation, and I thank you for bringing it in. I have often been asked why I focus so exclusively on contemporary art in my collection. Just recently, a journalist inquired about the oldest object in my collection. And because Karin Sander didn’t occur to me with her “Word Search” – this work was created one year after 9/11 – I cited the large text drawing “War Porn” by Fiona Banner that was produced in 2004. Because I only began collecting twelve years ago, I don’t own a single work from the previous century. I once said to a friend: “You know what? I believe I collect the present.” Not as an artistic era but as a state of affairs!” What is beautiful and paradoxical here is the fact that this putative present is already a thing of the past in the next second – you can’t preserve “now.” But what remains with the work of art is at least the memory of highly diverse “presents.”

I’m only really free when I neither specialize in something nor negate anything.

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

Are there works in your collection that have never been displayed in public?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

There is one space-encompassing work that indeed has never been offered to view heretofore. It is doubtlessly also the most personal work in the entire exhibition. It comes from the American artist David Horvitz who, in a process lasting six years, tried to guess the first name of my father. The back-story is that the original idea for this project comes from a work by Jonathan Monk. I was immediately enthused by the option of allowing Jonathan Monk as an artist to guess the first name of one of my parents, but the 30 000 euros he required for that purpose turned the plan to naught right away. It wasn’t until a short time later, when I met David Horvitz in New York and told him about it and he simply said, “I could do that for you.” That’s how it got started. Of course, this is almost a plagiarism, which however, we deliberately allow ourselves in this case. The fact is that Jonathan Monk is known as an artist for quoting and varying great pioneering thinkers and elements of Concept Art; we are also showing four relevant works of his in this exhibition at the Weserburg. So David and I considered it to be quite exciting to quote someone who himself quotes so often and so well. That has always occurred in music – and for a few decades now in the economy as well. Whereas Jonathan Monk would have written his guesses with a typewriter on normal paper and then sent them as a letter, I received e-mails from David. This crazy idea ultimately gave rise to a process that can now be retraced on a total of 421 printed pages and 387 name guesses.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

What if David Horvitz had guessed the name on the second try?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

Then the artwork would already have been completed with the second e-mail. Just as with Jonathan Monk’s original work, there were only three options for how the work can end: either David guesses my father’s first name or either the artist or the collector dies beforehand. So things could have gone on like that for a few more decades. But during the six-year project, there was an unexpected complication: my father’s name was Kaspar Schwarm. And “Kaspar” is also my second name, although until a few years ago I neither used nor communicated it. When our mother died suddenly and unexpectedly a few years ago, I decided to integrate my second name into my life from that point on – especially inasmuch as I was on the threshold of an exciting professional evolution at that time. It was clear to me that I had to inform David; he knew me only as “Christian Schwarm,” and extending my name in that way would raise questions for our name-guessing project. So I told him first that my father’s first name was also my second name, and secondly that I intended to start using it immediately; then I asked whether it was possible and desirable to continue with our project against this background. He had a simple and challenging idea and responded that he would “digitally avoid” me from that point on. He had to completely refrain from crossing paths with me on the Internet in order to be sure not to accidentally discover my second name or my father’s first name. No easy matter, considering that we both are quite active online and had been quite involved with each other in the past. But ultimately it was exactly this strange turn of events that crowned the work: it was only much later that I reread David’s first guess, where he wrote: “I guess that your father’s name is the same name as you. Is your father named Christian Schwarm?” As much as the second sentence was wrong, he was right on target with the first one. Nevertheless, it took six further years to solve the riddle completely. Magical.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

Accumulate, hoard, and stockpile: the stuffed storehouses of mega-collectors cry out for private museums. Christian Kaspar Schwarm, you are calling for a change in how art is collected. But how?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

What I wish for is less of a change in how art is collected, than a shift in how art collecting is perceived. That is an important distinction. What I mean is that various, often inapplicable stereotypes dominate our image of collectors: first of all, you have to be very wealthy in order to collect art. Second, art collectors are mavericks that are always in competition with each other. And third, collectors buy art only as a financial investment or as a boost to their social reputation. I’m not claiming that all these tendencies don’t exist, but I also know that many passionate collectors seek and find their art from an entirely different motivation. Professionals in the market confirm that the majority of collectors consist of dedicated and committed individuals who often are the ones to make entire artistic careers possible and who put their heart and soul into that endeavor.

The image our society has of collectors, however, is defined by a few so-called “top collectors” who, in a liaison with the media, engage in a tooth-and-nail fight over the most spectacular – and in some cases quite respectable – projects. And although I have absolutely nothing against that, I think it’s too bad when this image keeps many persons from embarking on the extremely personal undertaking of letting art into their life. It is for this reason that already in 2008 we established the international online platform Independent Collectors with the goal of democratizing life with art and motivating more people to involve themselves in that adventure. We present large and renowned collections online, but also share secret tips that almost no one is familiar with. This inspiring juxtaposition, this interest in the diversity of collecting is something that also brought us into contact with the Weserburg.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

When asked about the exorbitant prices and possible overestimation of art, Dirk Boll from Christie’s auction house replied: “Everything is still far too cheap. Art can’t be expensive enough, because it is unique.” How does that look from a collector’s perspective?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

That statement is of course absolutely biased and hence easy to see through. Art is unique, that is true. And I even agree that the value of an individual work can never possess an objective quality – neither in the highest nor the lowest price category. But I must say the claim that everything is “far too cheap” is utter nonsense. I would be tempted to respond with equal simplification that today there is unfortunately far too much unique art. When I am at Art Basel or at other art fairs, I often ask myself: who is supposed to buy all this? Especially since it represents only the tip of the iceberg. We can get used to the fact that 90, perhaps 99 percent of the art being produced today will not end up in a museum someday. So the most subjective criteria in making a selection continue to be the most valid ones. And remember: great art is available in all price categories!

What I wish for is less of a change in how art is collected, than a shift in how art collecting is perceived.

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

Lavishly embellished, personally recommended and limited in number: according to what criteria do you recommend 8 BOOKS A YEAR to an international reading public?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

With 8 BOOKS A YEAR, you are mentioning a project that I care about passionately and is also part of the Weserburg exhibition. In addition to art, I have long been enthused about very special non-fiction books. And I work almost daily with them. Together with my business partner Jone Szmania, I operate an office for creative strategy development. And because it was always my dream, we looked for a space that we could turn into a library. Now we are working in one of them – in a converted outbuilding in a back courtyard near Nollendorfplatz in Berlin. Because every month we discover new book treasures throughout the world, mostly produced by small, independent publishers whose output would never be found in a conventional bookstore, we had the idea of offering a curated book subscription. At first this was only for friends; then word got around, and meanwhile we send eight really fine books each year to people who like to be surprised and are ready to be confronted with issues that might otherwise never have crossed their path. It’s possible to join at any time and to receive eight books in the next twelve months by mail. By the way, we don’t earn money with this project; the effort and expenses are far too great in relation to the number of subscribers; but in return, we are able to share our passion for quite special books with like-minded persons throughout the world.

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

“I looked everywhere for peacefulness and never found it anywhere other than in a corner with a book.” Eco quotes what the mystic Thomas von Kempen wrote in 1418. In the protected space of a museum, without a smartphone, alone with a work of art: is there a more ideal invitation to engage in “reading”?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

Once again I am surprised how timeless a quotation can be – this time one that is even more ancient. One should make an effort to imagine what a book meant in the year 1418 – even before Gutenberg. It was precious, something quite different than today’s industrially produced books. Who could even read back then? And who made books? And why?

Nevertheless, I would like to mention something at this point that we are often confronted with in the library we completed only a year ago. We are frequently asked whether it is an anachronism, an old-fashioned pipe dream, to set up a library today in the era of the Internet. An artwork by Slavs and Tatars provides me with the best possible answer: we can appropriate all knowledge in a horizontal or a vertical direction. For me, horizontal means associative leaps from one point or theme to another. That corresponds to searching and researching on the Internet: I remain on the surface but quickly move from article to article. It is not without reason that we call that “surfing,” which is also a horizontal movement upon the ocean. Then there is “diving,” a vertical plunge into the depths. And in spite of the Internet, there is still neither a more effective nor a more efficient instrument than a book for really learning a lot quite quickly about a certain topic. It’s irrelevant whether one reads the book on printed-paper or as a digital copy. The issue is not “printed versus digital” – what matters far more is “breadth and depth.” And today modern libraries such as museums stand for this healthy balance. The Internet alone can never serve as a “high museum of breadth.”

We can probably live for three days without poetry and art – but an entire life without art is impossible.

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

CHRISTINE BREYHAN

I’m not asking how everything started, but instead how it will all end. “You can live three days without bread – but never without poetry (without art). And those among you who claim the opposite are mistaken; they don’t know their own nature.” Is Baudelaire correct?

CHRISTIAN KASPAR SCHWARM

We can probably live for three days without poetry and art – but an entire life without art is impossible. If art weren’t here, we would create it anew. Because we spoke about the reception of collecting, it’s important for me to say in conclusion that the concept of art should not be defined too narrowly. In addition to art and books, I am also interested in music, film, architecture and basically in all kinds of creative expression. Art admittedly has a privileged position and as a rule is created without being bound by a commission. But many musicians and filmmakers are also able to realize their ideas independently. My thesis for the coming decades is that all borders will become increasingly porous and hence more diffuse – and I’m looking forward to that! Already the Concept Art of the 1960s made a great contribution to us no longer considering art to be exclusively a matter of paintings or sculptures, and perhaps this is also shown in the exhibition of my young collection – there are a total of three paintings among the fifty or sixty works on display. If we were to repeat the undertaking in fifteen or twenty years, the result would surely be even more heterogeneous. We would then show things that to some extent already exist today – but with regard to which we are not yet in a position to even recognize them as art.