Independent Collectors

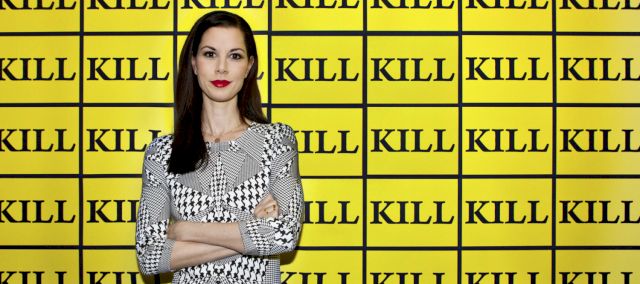

Julia Stoschek

Sergej Timofejev in conversation with Julia Stoschek: one of the most active and famous collectors of time-based art.

Collection of Our Time – Sergej Timofejev from Arterritory in conversation with Julia Stoschek: one of the most active and famous collectors of time-based art.

It was a sunny September day. Riga’s Old Town was full of tourists, and the air was full of expectation and promise. A group of people led by a young elegant woman quickly walked to the Riga Art Space building. Polite, self-assured, energetic, Julia Stoschek, who is a well-known owner of a collection of world class video art looked like a true leader of her team. Her education is in business and it is possible that her father a relatively important German businessman hoped that she would move in the same direction. Yet she chose a different path and, without a question, she has managed to establish it in a very businesslike manner: well reasoned and precisely.

It all started in New York, when in 2003 at the Gagosian Gallery she saw a video installation of Douglas Gordon, “Play Dead Real Time”: on a gigantic screen, a huge gray elephant, filmed in a minimalist setting of an abstract white hall, represented his own demise. The sadness and power inherent in this work impressed her so much that she spent in front of the screen that featured this 20-minute work that was repeated again and again about three hours. “This video was presented in a completely different format than all these countless black boxes that I had seen up to then,” she recalled. “From that moment on, art and collecting art began to shape my life.”

That is indeed a beautiful reference point, which is actually directly related to time. Twenty minutes and three hours. Time is an important component in the collection of Julia Stoschek, which already numbers about 600 works, and she calls it the collection «of the time-based art». Art that is based on time or using time – on the one hand, it is performances and action pieces and, from the other, video art and media art – formats where art is to some degree a process, where the moments of beginning an end as well as entering its field and staying in it are important. After all, it is impossible to evaluate the worth of a work in video by a momentary glance: it always requires from us some time, which we either are or are not ready to spend on it.

On the other hand, that kind of art expresses our time, the Zeitgeist, where the video camera is a part of practically every family’s equipment (and now is simply built-in in every smart phone or tablet) and a video recording is now as common as, say, the cutting of wood a couple of hundred years ago. “I collect video art because I believe that it is the medium of my generation,” Stoschek explains. Yet its global nature notwithstanding, this medium turns out to be quite fragile in face of — yes, time, because these works are recorded with a certain technique and with the help of particular technologies, which age fast and are replaced by new ones. Julia Stoschek collects not only original works, but also the relevant equipment – the whole thing. For such a collection thus a large and well thought out space is a must where any interested party could view it (to share and show these works is one of the most basic intentions of this young but very goal-oriented collector). In 2007, in her native Düsseldorf a building was unveiled that had been specially designed to turn a former factory into exhibition space. Thematic exhibitions take place there regularly, highlighting one series of important works or another from her collection. Yet they are exhibited not only in Düsseldorf – a part of them are now on display in Riga where they, represented by true highlights of the collection, its most contemporary part, can be seen under the title High Performance. We talked to Julia Stoschek right there, in Riga’s Art Space. After she had walked through the entire exhibition with her colleagues, making sure that the exhibit looks respectable and feeling happy about it, we sat down to talk behind a round table adorned by a couple of bottles of mineral water.

SERGEJ TIMOFEJEV

Do you consider video not only a contemporary but also an essentially political medium?

JULIA STOSCHEK

First of all video art is to me a very interesting medium because of its synaesthetic qualities – there is sound, moving images and sometimes narrative elements. However moving image can maybe better than other kinds of expressions reflect on political circumstances or movements in society, because it is more precisely and more direct. I can’t speak for the artists themselves, but I think, that the engagement with political aspects is always part of the development of an artist and it is also very important to generate their own point of view.

Do you make a point in collecting that kind of work?

The collection does not have a particular theme. The concept behind it is to show the development of video art since the beginnings in the 1960s to the present. For that reason, I am very much interested also in works that are already “historical”, like those of Bruce Nauman, Gordon Matta-Clark and Vito Acconci for example. I like this juxtaposition of the recent past and the present. On the other hand, I find it interesting to follow an artist’s development over a longer period. I am trying to connect to his or her creative trajectory and to choose the best works from different periods to form an overall impression about his or her individual path and approach.

I am very much interested in works that are already 'historical', like those of Bruce Nauman, Gordon Matta-Clark and Vito Acconci... I like this juxtaposition of the recent past and the present.

JULIA STOSCHEK

If you begin your collection with the art of the 1960s, I would like to ask you how you formulate for yourself the difference between the experimental filmmaking that existed until the emergence of video art and the video medium?

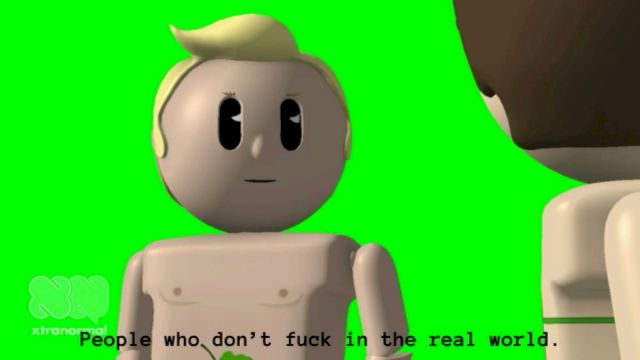

I am not a person that would categorize or label everything. I am often asked wherein lies the difference between cinema, film, music videos and video art. For me, honestly, this is not really important. For instance a wonderful music video in 3D for Björk by Encyclopedia Pictura is in my collection. I consider it a work of art.

I really like the term you use to characterize your collection, time-based media art. Can this art say something new and interesting about time itself?

Of course. We live in the digital era and the spirit of the times plays an important role in my collection. Since Gutenberg invented the printing machine, there has been no radical change in the history of mankind comparable to the emergence of digitalization and the Internet. And the ephemeral quality, the impermanence and the determined development of our era seem to me best represented by the moving image. In addition, it is important to me to develop the cultural and emotional history of my generation. That is why I collect these works.

How has your personal relationship formed to video as a technology and part of the contemporary lifestyle?

I was born in 1975 and grew up in the era of video and MTV; my father always liked new technologies and the opportunities they offered, so we would of course have a video camera at home. That´s how many personal moments of my life have been preserved on video. The medium then became something quite familiar and also closely linked to my personality – I guess I simply love the dynamics of the moving image!

I am often asked wherein lies the difference between cinema, film, and video art… For me this is not important… a wonderful music video in 3D for Björk by Encyclopedia Pictura is in my collection. I consider it a work of art.

JULIA STOSCHEK

What served as the first impulse for forming your collection?

I lived in New York studying business and economics, but I was also interested in the local art scene. And one day I walked into this gallery where I saw the very first video installation of my life. It was a work by Douglas Gordon in which an elephant played his own death. This was the three-channel video installation «Play Dead Real Time». I stood and watched it for a long time. This was a powerful moment, which had a great impact on me for my later decision to become a collector. Other collectors influenced me as well, for example, Harald Falckenberg from Hamburg and Ingvild Goetz from Munich. She was one of the few female collectors and the first to focus on time-based media.

Do you have a special interest in what female artists are doing, that is, in feminist art?

I wouldn’t say that it’s a priority for me. I am interested in art as such, whatever the gender of the author might be. We just had a show of Elaine Sturtevant and tomorrow we are opening an exhibition of Elizabeth Price. The next one planned is with Trisha Donnelly but all of this is rather a coincidence. Actually, if we look at the history of the genre, in the 1960s most of the first works in video art are recordings of performances, which are first and foremost related to the body and many of them were made by female artists who found this theme most important at the time. That is, the genre seems historically to have a certain feminist quality. But as I already said, I prefer not to think in such categories.

Other collectors influenced me... Harald Falckenberg from Hamburg and Ingvild Goetz from Munich... one of the few female collectors and the first to focus on time-based media.

JULIA STOSCHEK

You not only collect this art but also preserve it for future viewers…

Yes, the theme of conservation and preservation is of great importance for the collection. It requires much effort and financial investment. Still we do not only preserve but also show art. In the Düsseldorf space we have continuous exhibitions running most of the time showing works from the collection in different presentations. In addition, the works and the exhibitions travel and are shown in various places and contexts, just as here, in Riga, at Riga Art Space. For me, collecting does not mean just acquiring art but also presenting it to the public. I´m very glad the works are here in Latvia right now and will be seen by a completely new audience and – hopefully – become part of their cultural experience.

Many collectors talk about their very personal relationships with this or that object from their collection. Is it like that for you as well?

I have a very personal relationship with each of the works in my collection. Here in Riga a work by Aaron Young involving a motorcycle that is permanently revolving on the spot at full speed is exhibited. Its title, *High Performance*, became the name of the entire exhibition. The piece is in fact the very first video work that I ever acquired. And I have that kind of relationship to all of the works – sometimes it has to do with some significant situation in the artist’s studio; at other times it has to do with some specific gallery, city or place.

What are some other differences between this and more traditional types of collecting?

Much effort goes into the exhibition of works. To transport them is relatively easy, you simply take the disks with recordings with you. But to exhibit them in an appropriate space, with good sound, is rather complicated and takes time and effort in the planning and the realization. Maybe that is why not so many private collectors get involved with this medium, in contrast to specialized and experienced museums, which purchase such works for their collection. But that makes no difference to me.

I am not a dealer, I don’t want to sell the works... Time-based media art is not the most popular sphere for investment or speculation.

JULIA STOSCHEK

It is probably important to create conditions in which the viewer would find it comfortable to linger in front of the video work, to spend time with it. In this sense, it would be interesting to find out more about your exhibition space in Düsseldorf.

It opened in 2007 in an old factory building erected in 1907. It is a wonderful industrial building. We have two floors of exhibition space and in the basement there is a special screening room. There is also a cinema for 16 and 35mm films. We have a library and an office. The entrance to our exhibitions is generally free. The free access is something very important to me. Visitors are welcome every Saturday and Sunday. Also we offer guided tours free of charge.

Collecting is of course connected with the art market, with the cost and value of works. Do you think that the value of video works will increase in the future?

As I said, I studied business and economics, but my interest in collecting is not monetary based. I am not a dealer, I don’t want to sell the works. Of course, the prices of masterpieces have constantly gone up. Time-based media art – fortunately – is not so popular on the secondary market; luckily it is not the most popular sphere for investment or speculation.

What has collecting brought to your life and to your lifestyle?

That is quite a personal question to me… (*Laughs*). You know, I am a very emotional person, an enthusiast and I think it’s my fate. What can I say? … (*Laughs*). I am in love with this art form and I am more than happy that the collection exists and that a wonderful group of people is helping me to take care of it. I am a lucky person. And I like to show art works and to observe the interest of viewers, as it was in Budapest or Kiev a few years ago where the exhibition was extremely well received with about 2000 visitors a day. Art sends out a signal of freedom and independence – and that is what really counts for me. For that reason it was very strange to encounter attempts of censorship at Manifesta in St Petersburg where the collection was invited to show works in a film program. Unbelievably problems came up with showing a work related to the performance and the body of an artist – namely *Art Must Be Beautiful. Artist Must Be Beautiful* by Marina Abramovic. And it was all because of the nakedness involved. But you know, just take a walk through the Hermitage and you will run into, say, a nude by Rubens and all these other works involving nudity. Yet it seems to be prohibited to show nakedness in more contemporary works like moving images or photographs. But that’s Russia – here in Latvia we did not encounter anything like that. Luckily the democracy here seems pretty in tact and as a member of the European Union will hopefully remain so.

If a video is subject to censorship and is prohibited, does it then mean that it possesses the potential of free-thinking?

Yes, of course. And it is important to me. Let us fight for the freedom of art!

This interview was originally published in Arterritory’s “Conversations With Collectors, No. 3”

For more information visit JSC.