Independent Collectors

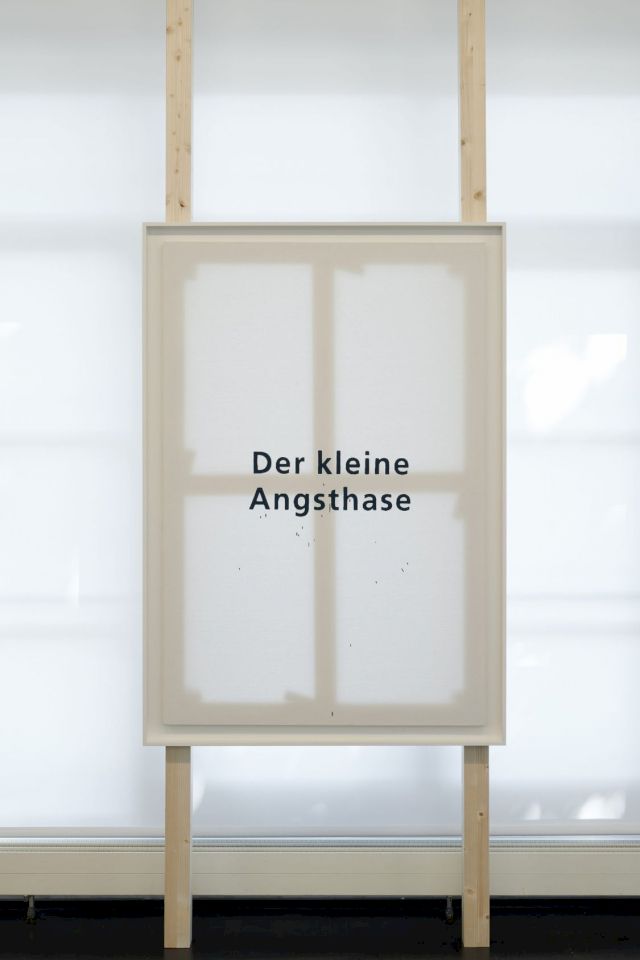

Oliver Osborne: Der Kleine Angsthase

We’ve all experienced fear this year. The exhibition DER KLEINE ANGSTHASE at Braunsfelder, curated by Nils Emmerichs, presents works by Oliver Osborne, as well as a conversation with Nicolaus Schafhausen.

Fear is one of the strongest emotions. Fear feeds on lived experiences, on unlived anxieties and makes use of all means at its disposal. It uses common threats and discomfort to the same extent as it invents new ones. It reproduces and produces at the same time, it copies, quotes, counteracts, records.

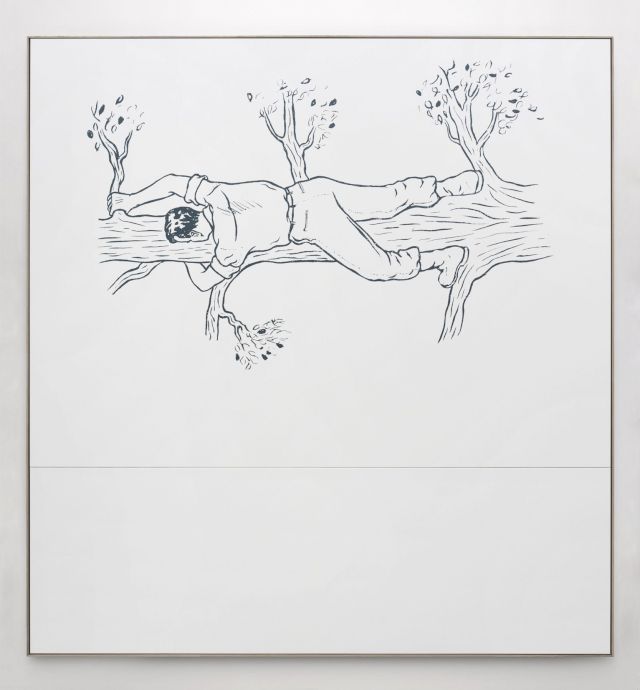

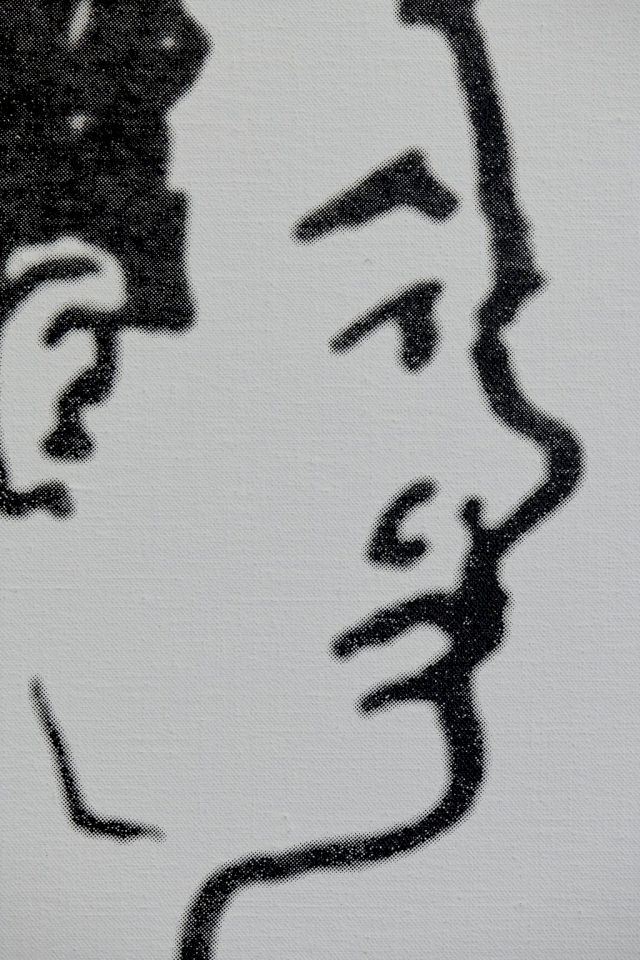

Oliver Osborne understands Elizabeth Shaw’s children’s book Der Kleine Angsthase (1963) both as a carrier and as the object of his message, and thus discovers symbolism as a painterly tool, which no longer becomes just a medium but a subject for him. He directs attention back to that which threatens to disappear in the transparency of the painterly image: he refers back to the image.

The first, next and probably most important environment of a painting are therefore other paintings. Our pictorial history consists of stories, places, objects that are memorized through thinking. Oliver Osborne’s pictorial worlds are paradoxical in a fascinating way: signs and motifs are recognizable, but what he wants to show often remains deliberately open. There are traces that we follow, references that we read, but in the end it is the precise painterly gaze that makes us think about the realities and possibilities of his conditional representation.

Nicolaus Schafhausen in conversation with Oliver Osborne:

“To visit artists in their studios is fundamental for my research. It is always most exciting to discover the unknown. Welcoming guests into the private sphere, thus exposing the intimate can often spark certain insecurities, even fear – but is fear not one of our oldest and deepest emotions? When I learned that Oliver Osborne’s exhibition at Braunsfelder was to deal with Elizabeth Shaw’s children’s book “Der kleine Angsthase” (1963), my curiosity was instantly triggered. I initially encountered his work during his solo exhibition at Bonner Kunstverein in the spring of 2018. What struck me were those inherent moments of continuous reflection of the self as well as his profound observations on image and language. It was not until the spring of 2020 that Oliver and I met for the first time in his Berlin-Neukölln studio. In addition to my previous thoughts, I encountered an artist who is not afraid to think distinct and meaningful ways of painting.”

Nicolaus Schafhausen

What do you fear most?

Oliver Osborne

I try to fear only the things that pose me a threat, which is to say I think we should try not to fear the things that pose none. I borrowed the title for this show from Elizabeth Shaw’s German children’s book Der kleine Angsthase (1963), which is superficially a story about bravery: the Angsthase overcoming his fear to defeat the fox and save his little friend Ulli. Angsthase fears the things his Oma has told him to fear: dogs, robbers and ghosts, drowning, the bigger rabbit children – all logical threats for a rabbit. So why the later pressure from his uncle to overcome a fear of things he has been told to be afraid of? It’s misleading.

What if the fear/bravery dynamic posited by stories like Angsthase is bogus? A self-perpetuating playground masculinity that favours the bully and demeans the cautious. Rescuing Ulli is an act of love – it is not the emancipation of a once timid rabbit.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

What is your biggest hope?

Oliver Osborne

Time? Time for more possibilities. Time to see what the accumulation of it all might mean. Time to filter. Time to start again.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

What do you need in order to work?

Oliver Osborne

Hope? The feedback loop of self-doubt doesn’t (I’m guessing shouldn’t) get any less difficult the longer that you get to work as an artist. But somehow, and perhaps it’s naive, the hope keeps returning. The feeling that progress is possible. In The Hatred of Poetry (2016) Ben Lerner jokes that the poet is still writing poetry, when most other people have grown out of it. So let’s make something today, and everyday, and then for years, and now with some more rigour and criticality. And on and on. You need this instinct and it requires hope. And then you need a certain amount of infrastructure, and that’s a more adult negotiation.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Are you able to express your truths within your artworks?

Oliver Osborne

Perhaps not immediately. Many of our impulses or inclinations (in how we present ourselves) probably come out of a desire to negate our truths as much as to reveal them. But I would hope that as we work, incrementally, we can gain an understanding of our predilections and learn the confidence to reveal certain aspects of our personality. Art school, for example, is often characterised as an open, free forum. But the experience is just as often one of survival – as you receive some kind of training, you’re constantly shielding vulnerabilities at the same time as learning to access the experiences that could inform your practice. It is quite performative.

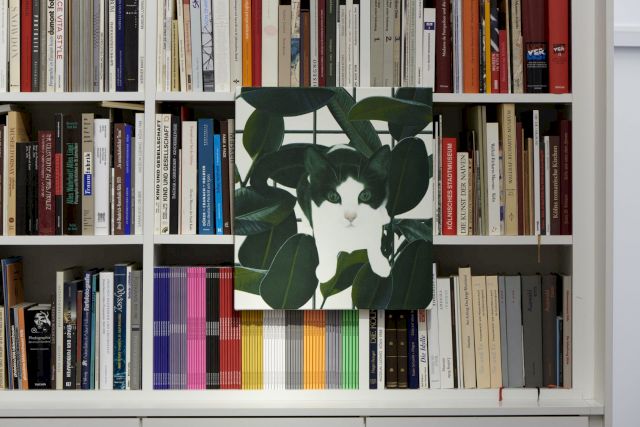

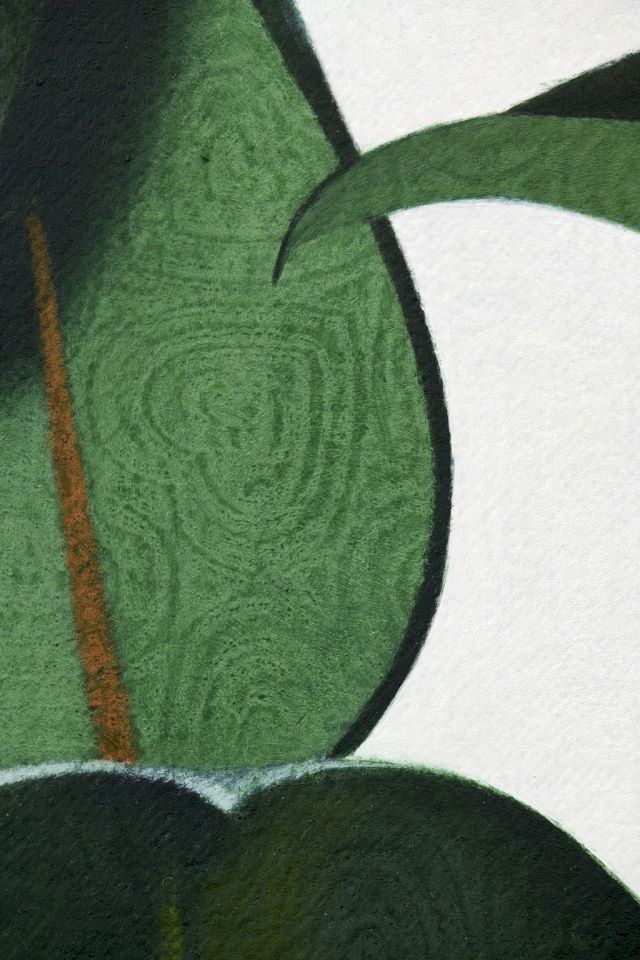

Many of the ways in which I have worked may have begun with that coy, defensive mindset but with time they can become more honest. I began making the rubber plant paintings eight years ago and it is a subject, with varying degrees of intensity, I keep returning to. Restricting myself to adding slow, meticulous pictures to a culture of much higher speed images can breach a gap where formal considerations and external reference combine to produce an image of pertinent specificity and rigour. As these works begin to accumulate and find some kind of place in the world, perhaps then they might begin to express something like a truth.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Your work is handmade and controlled. Have you ever thought about formally breaking out?

Oliver Osborne

I think of it being more like breaking in. When I started using academic oil painting techniques, I felt like I was appropriating something and that this way of painting spoke a language that could get me closer to a place that people might recognise as a kind of painting whose behaviour they thought they knew. A kind of painting that would meet their expectations, and that by working with these preconceptions that people have around painting I might be able to disarm them and smuggle some other more problematic ideas in. If I could get control of that, control of painting as a language with its own grammar, then I’d have room to move outwards from there.

What I do is only handmade when it needs to be, but it is definitely controlled. When I was studying I internalised an idea that every physical element of an artwork was a decision, and therefore a position, and so there had to be something like accountability at all times. But here I am speaking just about the material properties of the work – I would hope that content or imagery I might work with could have trajectories that are out of my control. Perhaps some artists approach this the other way around.

There’s a crossroads that I’m usually trying to arrive at where in one direction you have the formal properties of the paintings in which my processes are clear, conforming almost to genre or type, without any kind of obfuscation. Here every haptic inflection is deliberate, intended and considered. Meeting this is something like the content, like the rubber plant or a piece of text or a graphic image. Again these things are nameable and specific, usually of a kind of middle order, non-exotic register. I can dictate how a painting of a rubber plant is presented, I can dictate that you recognise it as a rubber plant, but I cannot control what meaning such a painting might accumulate and this is where I cede control. The images I work with are always of this order – so in this show for example there’s the cat painting. It is google’s cat, everyone’s cat, and what I think that means is of a lower interest.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Painting is a process that requires time. Where, in your work, does “process” begin, where does “process” change, how does “process” go forward and backwards?

Oliver Osborne

Painting, or the practice of painting, is incremental. Like a technocratic approach to government it requires pragmatism and patience. Though larger, fundamental change should never be discounted.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Frank Stella or Robert Ryman created bodies of work that understood colour and form in a new way. They regarded painting as of form of denial, or a thinking against modernity. Do you include similar thoughts in your painterly process? How do you use colour and form? When do you regard a painting complete?

Oliver Osborne

I think it sometimes helps to think of painting as a technology and how despite its high cultural position it has perhaps only once (with single point perspective) been at the cutting edge of what humans were working on. This is not true (for example) for sculpture, which keeps coming in and out of line with a technological leading edge. So if this is true, how did painting achieve such an exalted position? It possesses a different kind of potential.

But I’m ambivalent about whether I might understand colour or form in a new way because it’s out of my control – you may say I do or I don’t – but I do get excited when a painting I’m working on begins to feel like something that already existed, like it has come to me fully formed. At this point the part I played, the steps I took, start to disappear and the work takes on an enigmatic charge.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Can we think art history (especially painting) after 1945 anew? Should we start with the contrast between painterly self-invention and partisan mythmaking in the life and work of artists?

Oliver Osborne

I think we should all be wary of ways in which exhausted twentieth century tropes are reinvented by contemporary artists. We have to think harder about those things that are exhausted and why. We have to consider that in the West artists trained in the history of an avant-garde art occupy a majority, not a minority. Contemporary Art is a part of mainstream culture. This wasn’t always the context that young artists found themselves in and its flaw could be the professionalisation of the industry. But acknowledging these things shouldn’t preclude an urgent, fundamental re-evaluation of art history. I believe the artists, curators and writers of my generation are heavily invested in this process.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

I have noticed that certain painters have a talent to be theatre painters, in that they retain an overview in front of a giant canvas. Are you good at that? Have you ever thought about it? Do you have a sense of proportion?

Oliver Osborne

I can relate to that impulse. I’ve never really been a theatre goer but I’ve always liked billboards, and considered them painting’s accidental analogue to public sculpture. But I think we need to rethink what scale or proportion means in this century. There’s a story of scale and painting that could take you from Diaghilev, Picasso and the Ballet Russes to Michel Majerus re-skinning the Brandenburg Gate in 2002. Let me expand: during renovations Majerus covered the Brandenburg Gate with the facade of Berlin’s brutalist (anti) icon Das Pallaseum (1974-77). Also know as the Sozialpalast, it was built on the site of the Sportpalast, where in 1943 Joseph Goebbels declared total war. Majerus’ re-skinned facade coincided with that September’s German Federal elections, when Gerhard Schröder’s Red-Green coalition narrowly retained its majority. Majerus’ work became backdrop to the global television coverage of the election. It marks a high point in Majerus’ project to reimagine his commitment to art history in the context of an exploding, digitised mediascape. Majerus was understandably tickled to find his work on CNN and other networks in the heat of an election battle and it is fitting that the explosion in scale that art enjoyed during the twentieth century should reach a climax on television (and in Berlin). Today scale is something more complicated, proportion relates now as much to digital space as it does to physical space, and Majerus offers an important key to how artists first began to understand this shift.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

What constitutes an artwork’s value, if made solely to order and for the market, rather than to aesthetically educate the viewer?

Oliver Osborne

In my experience, the market doesn’t express its desires as directly as you imply. And I’m not sure there should be such a hierarchy between artist and viewer. What I do enjoy is the imbalance in our fluency with art, between artists and their audience, between generations. This creates opportunities where understanding and expectation differ, and perhaps it is this friction that produces value.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Does an artwork remain authentic when it is no longer assessed for its creative process, but only after its completion?

Oliver Osborne

I don’t know. ‘Authentic’ is problematic for me. I’m constantly trying to establish for myself how you might present something honestly whilst simultaneously and paradoxically acknowledging the artifice of art making.

To go back to Majerus, when he died, this hugely prolific output was suddenly extinguished. But something latent in that work keeps working, and the pressure keeps building, and a new generation (including me) become interested, inspired, and his works take on more meaning. Two decades distance is not making Majerus any less authentic an artist.

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Why do artists rarely succeed in emancipating themselves?

Oliver Osborne

Does emancipation not require a complete rupture from the place you began? Perhaps artists, like most people, are not able to contemplate that?

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Why is the “myth of the artist” increasingly replacing his/her work, even though it is persistently maintained that the artwork speaks for itself?

Oliver Osborne

There are many different dimensions to these kind of myths and we shouldn’t lose sight of whose interests their creation might serve. I’m not here to defend myths. Annoying word, but maybe that’s why we admire the oeuvre, the body that is greater than the sum of its parts. To make art you probably need to self-mythologise to some extent, but there is a kind of magic in working and working, mostly plodding or struggling, and then suddenly little things happen and ideas fall into place and a work turns out as if it has arrived fully formed from elsewhere. You were present the entire time, and yet there it is, close to new, a complete surprise.