Independent Collectors

Collecting the Elusive

In a small project space near Istanbul’s Taksim Square, Özge Ersoy and Haro Cumbusyan investigate into the complex world of collecting by bringing private art collections to the public view.

Each presentation at collectorspace consists of three principal components:

– The exhibition of a single artwork from an acclaimed private contemporary art collection.

– A video interview with the collectors that documents their collecting practice.

– A publication that presents the collection to critical review with commissioned texts by outside writers.

Here on IC, Özge Ersoy shares installation shots, video interviews, and texts from the collections that have already taken part in the project, all of which continue to challenge the meaning of collecting art. Featuring the Aarons Collection, New York; the Gensollen Collection, Marseille; the BAS Collection, Istanbul; the Stilpass Collection, Cincinnati, and the Cervantes Collection, Mexico City.

COLLECTING THE ELUSIVE – ÖZGE ERSOY

That abstract term in contemporary art, “value”, does not rely on permanence nor uniqueness anymore. We see art that consists of fleeting ideas, performative stories, momentary gestures at numerous biennials and museum exhibitions. Art institutions follow this wave of change, giving more and more space, time, and resources to this particular breed of artistic production—they continue to think about how to collect and preserve these works. How do private art collections respond to these shifts in today’s art world?

Collecting art is often understood as a practice of accumulating “tangible” objects—though there are a number of private collectors across the world that break this traditional assumption. These collectors buy ephemeral, temporary, or non-object-based works, and it is with this attitude that challenges what it might mean to “own” art. But, really, what do you actually ever own when you buy an artwork?

For the last four years, my colleague Haro Cumbusyan and I have been running a small institution in Istanbul, located in a storefront that overlooks Taksim Square. We deal with questions such as “how to collect live art?” or “how to end a collection?”. What we aim to do is to initiate conversations about what collecting could possibly mean in a living ecosystem like that of contemporary art. In our pursuit, we collaborated with inspiring people who developed idiosyncratic contemporary art collections, provoking different questions with every exhibition we organized. Each exhibition consists of a single artwork from the collection—“a solo exhibition for an artwork.”

Below is a selection of five of the forward-thinking collections that continue to challenge the meaning of collecting art. A small collection of the collections.

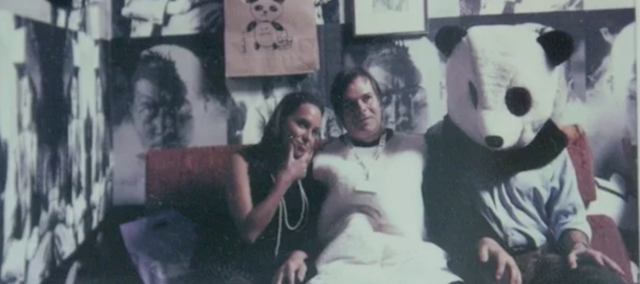

RYAN MCNAMARA AND THE AARONS COLLECTION, NEW YORK

Ryan McNamara’s work, which we borrowed from the Aarons Collection in New York, was quite curious—it’s an artwork that acts both as an archive and a performance. ‘And Introducing Ryan McNamara’, 2010–ongoing, is a personal archive that the artist has been building since his childhood, including photographs, drawings, prints, stickers, and posters. The only way to activate the work is that McNamara puts the items in this archive in front of an audience where he tells stories about them. The work is not present if the artist or the audience is not there. McNamara joined us at collectorspace to perform his piece, and before he did so he asked us to send out a personal invitation instead of a press release. “I will be in the project space, equipped with photos, videos, and memorabilia dating from my birth to April 2010, waiting to familiarize others with my early years,” he wrote, “I’ll give you a tour, talk about things that matter (or have mattered) to me; hopefully, if all goes as planned, you’ll reciprocate.” The artist customized his time according to every single visitor, be it a two-minute or a two-hour tour of his archive. “Performance is a moment in time. You have to be there at that moment. If you’re there, you see it, if you are not, you miss it—maybe you’ll catch the next one,” says collector Shelley Aarons. Philip and Shelley Aarons have an interest in temporary artworks, or works that decay over time. That said, how could a private collector accumulate moments and grow with them?

JULIEN BISMUTH AND THE GENSOLLEN COLLECTION, MARSEILLE

Based in Marseille, Josée and Marc Gensollen, both practicing psychiatrists, bring the main characteristics of their profession into their collecting—they accumulate works that are based on language, dialogue, and process. Their collecting practice poses a very specific question: How do you change the idea of ownership when collecting works that are based on encounter, conversation, and performance? This question was essential for ‘Mime Works I-IV’, 2010, a work by Julien Bismuth, which we borrowed from their collection: What remains after the performance is over and who actually owns a live artwork? Bismuth collaborated with the mime artist Gregg Goldston (who in turn trained an Istanbul-based mime artist, Eric Wilcox) to activate his half-an-hour performance at least twice a day for the duration of the exhibition, which lasted about seven weeks. The mime artist on the “stage” climbed on the spiral stairs, reminiscent of Alice in Wonderland, squeezed his body into tiny boxes, fell off a cliff, and took on different personalities that encounter each other in a gallery space. The mime artist argues that he is the owner of this performance, as it is primarily his body that knows the work. Asked a similar question, the Gensollens answer the question: “Couldn’t ownership mean to simply disseminate an idea?”

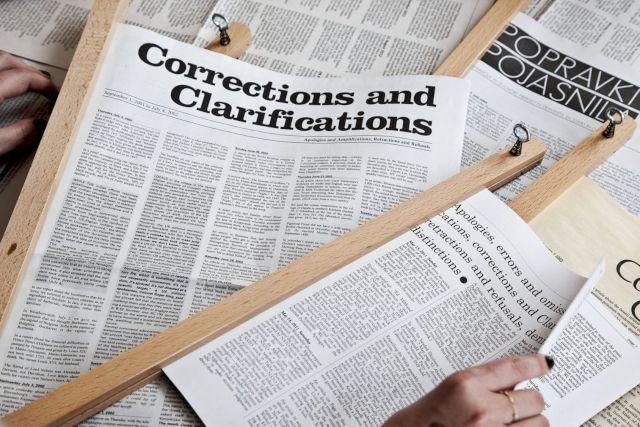

ANITA DI BIANCO AND BAS COLLECTION, ISTANBUL

Initiated, developed and run by artist Banu Cennetoğlu, the BAS Collection belongs to a rare species. Located in Istanbul, Cennetoğlu asks: What kind of a value do you assign to a collection with “non-precious” works that are produced in large editions? To engage with this question, collectorspace hosted “Corrections and Clarifications”, 2001-present, an ongoing art project by Anita Di Bianco in the form of a newspaper. Di Bianco started this work in 2001. The project has thus far more than 15 editions published in different languages in different locations. For each edition, she made a selection of corrections printed in daily newspapers, published in large quantities, distributed free of charge. “Non-precious” works like Di Bianco’s are not usual items belonging to private collections, as private collections don’t often include works of multiple editions, circulating in and out of the mainstream art channels. Here, BAS proposes a strong alternative to a value system that prioritizes unique and precious objects to aggregate value. BAS embraces all the works that are offered to the collection—an open acquisition policy in buying, accepting and bartering works, creating a diverse selection rather than a selection based on personal taste.

LIAM GILLICK AND THE STILLPASS COLLECTION, CINCINNATI

Andy Stillpass is one of those collectors who favor small gestures that accumulate over time—and he accumulates with the artists. The work we borrowed from the Stillpass collection is a case in point. Liam Gillick’s ‘Exterior Concourse Diagram (trad. Celtic circa 200 A.D.)’, 2000, a wall painting with a bold, multi-colored geometric pattern, is applied to one of the exterior facades of Stillpass’s home in Cincinnati. The work responds and redefines the space it inhabits; it refers to a meeting point, an environment with a get-together activity. Since the late 1980s, Stillpass invited many artists to his family house—a generation that is interested in what we would now call Relational Aesthetics. The artists came and realized small-scale gestures and spatial interventions over time, responding not only to their environment but to each other as well. With these commissioned works, the house has over time turned into a unique art installation with works that cross-reference each other and stories that weave together both the collection and the close relationships between the artists and the collector. Stillpass Collection is a proof that the collector can act more than a commissioner, becoming a creative impulse in artistic production.

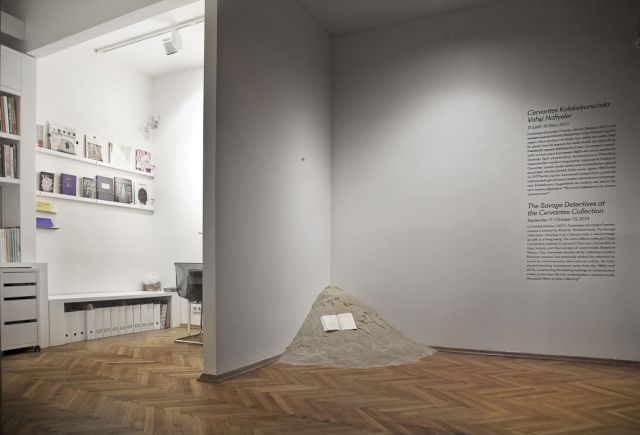

DOMINIQUE GONZALEZ-FOERSTER AND CERVANTES COLLECTION, MEXICO CITY

What we borrowed from the Cervantes Collection was simply a temporary combination of things. ‘Untitled (Bolaño)’, 2011, by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster was reconstructed at collectorspace with 300 kg of fine sand that we found from a construction company and a copy of Roberto Bolaño’s ‘The Savage Detectives’, 2013, that sat on top of the pile, open to a particular page. The pattern on the wave mimicked the one on the open page—a wave that could slowly disappear every couple of days due to the nature of the sand (Requiring us to redo the “work” from time to time). With this work, Gonzalez-Foerster creates a temporary habitat for this book; she treats it as a literary text and as a living organism connected to its environment. Based out of Mexico City, Cesar Cervantes’s aesthetic sensibility is similar to Gonzalez-Foerster’s attitude. The Cervantes Collection is similar to a living organism, open to temporary couplings/togethernesses that are bound to dissolve over time. Its value then comes from ephemeral co-existence with the works (conceptual works dating back to 1960s), as Cervantes asks the unusual question: When does a collection come to an end? After all, an art collection does not have to be different from a book or a film. As long as it’s able to tell a good story, it might as well come to an end.