Independent Collectors

Art Now, Art Forever: Damon Zucconi

As collectors dedicated to following artist careers in depth and breadth, Clayton Press and Gregory Linn describe their on-going relationship to the work of Damon Zucconi, whose works are frequently accessible online.

The art of forever is technological. It is an avant-garde medium, pushing the boundaries of both conceptual and visual art. The medium is made, if not engineered, to be accessed from a digital repository. It is entirely portable and can be viewed anywhere at any time on any electronic device in its original and intended form. This is among its several triumphs. It challenges every other medium—drawing, painting, photography and sculpture—that can only be “reproduced” online.

Garden, 2020 (https://garden.work.damonzucconi.com/) by Damon Zucconi (https://www.damonzucconi.com/) is delivered and sustained via a web address or url. There is neither a specific entrance to nor exit from the work. The work’s visual complexity is multi-layered; each encounter is mesmerizing. You can land on a visually textured image that looks like tapestry. It then changes to an image of a dog resting in the garden, only to invert and dissolve into a checkerboard overlay on a bed of flowers.

(To access the artworks presented in this IC Online Exhibition, please click on the hyperlinks in the text, indicated with an underline.)

The creation of Garden warrants explanation. Zucconi has built an ever-expanding data base of images that he photographed in his pocket-sized, Philadelphia garden. This sometimes-unruly patch of urban habitat is also the domain of Polly, an adopted (and much loved) Chiweenie. (She frequently appears in this work.) Garden is a computer program that randomly samples database images which morph every 10 seconds or so—from dazzlingly intricate digital patterns to subtly transformed full screen stills.

As the program selects images from the database, it creates one of millions (very high millions) of visual permutations that hover between abstraction and representation in a neverland of combinations, repeating that process every few seconds. The actions in the process may include:

- – Different sized grid masks are generated and a grid size is chosen

- – Either 2 or 4 images are randomly selected and merged using the masks

- – Images may be rotated along 90-degree increments

- – Hues may be rotated along 90-degree increments (yellows become greens, greens become blues, blues become reds)

- – A specific strategy for hue-shifting is chosen per mask

A few different computational strategies are also at play. Each operates a little differently, yielding different visual output. Zucconi’s program coding invites John Cage’s “chance operations” to wonderful effect.

+. +. +. +. +.

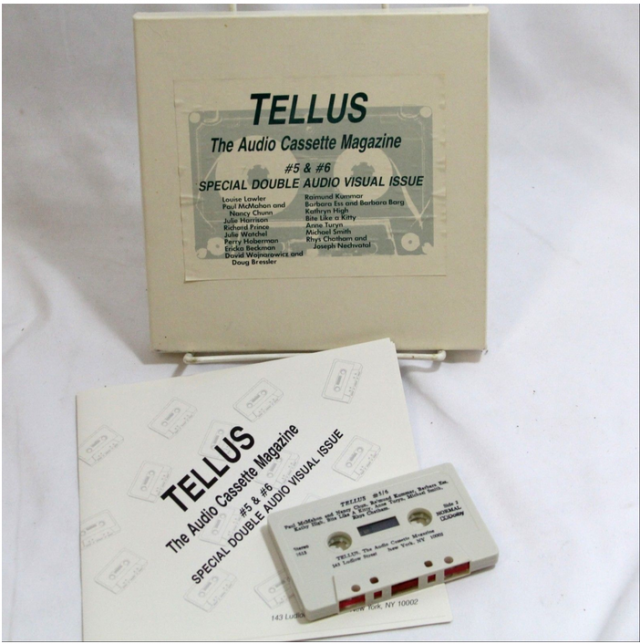

As collectors, we were open to art that was technologically based or derived, and we became early adventurers in new media. We began as subscribers to Tellus, a bi-monthly subscription publication of audio art and new music that was available between 1983 and 1993. The publication was both witness to and a participant in an evolving analog-to-digital revolution in new media. Charles Eppley, an art historian at Oberlin College and Research Fellow at Bell Labs, suggested that Tellus was a reminder of the “mobility of sound,” [that it] “can travel, move, and work itself into a number of spaces, networks, and rifts cordoned off to other artistic mediums.”

The first issue of Tellus that we bought included Louise Lawler’s Birdcalls, 1972, a 6:52 minute recording, that was later republished in 1984. Lawler pronounced the names of 19 artists like bird songs and calls. (“Songs are used to defend territory and attract mates,” according to Audubon.org). Birdcalls was a prescient work. As Eppley explained, “Lawler’s piece plays on the ability of sound to occupy many spaces, sometimes simultaneously, including the gallery.” Since most art was static, confined to homes, galleries and museums, the ability of art to “occupy many spaces” was an inviting concept for us.

We next embarked on collecting numerous artist cassettes from Tellus, many of which were music. Video tapes (Beta and VHS) followed. We could pop them into a machine and play them. Because most of the works we collected were and continue to be non-narrative, they could typically be played in repeat mode.

We encountered (saw and heard) Stan Douglas’s Hors-champs, 1992—a tribute to the Free Jazz movement of the late 1960s, using a double-sided screen projection—when it was shown at David Zwirner Gallery in 1993. With regard to time-based media, the work was something of an epiphany for us both. Shortly thereafter, Zwirner presented Sampler–Southern California Video Collection 1970-1993, a 24-artist exhibition of videos organized by Paul McCarthy. The breadth of content and delivery was revelatory. But our interest in and commitment to time-based media was secured with Diana Thater’s first exhibition with David Zwirner, Late & Soon (Occident Trotting). This encounter led to our purchase of Thater’s Pape’s Pumpkin, a unique, 1994 two-monitor installation. It triggered a complete rethinking of how video could be presented domestically.

With nine video installations, several CD-ROMs and USB flash drives, and numerous drawings by Thater, she is a cornerstone artist in our collection. (All of the works are promised gifts to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Our collection of new media art evolved. Throughout the 1990s we looked, we saw, we decided. Starting with Diana Thater, our collection of video art came to include: D-L Alvarez, Stephan Dillemuth, Fischli and Weiss, Christian Jankowski, Joan Jonas, Mike Kelly, Mark Leckey, Christian Marclay, Paul McCarthy, Jason Rhoades, David Robbins, Kay Rosen, Borna Sammak, Katy Schimert, Franz West, TJ Wilcox, and Jane and Louise Wilson. In our minds, new media was not that far removed from home entertainment technologies. We learned to read instruction manuals, resulting in a few more buttons to push and cables to plug in.

The next step in new media was Internet based. We were introduced to Zucconi’s work by Jasmin Tsou of JTT. Our response was immediate, positive. After looking at Zucconi’s URL works, we commissioned an Internet-based work, a JavaScript URL, that functions like a digital calendar. It displays the passage of days since we first met on February 29, 1980. In a sense, the work is pure biographical abstraction rendered by an algorithm, marking the passage of: years, months, weeks and days, but never—never—is it strictly about time. Like On Kawara’s Today series (date paintings) and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s biographical text paintings (the latter were also commissions), xxith.com multiple records a date that triggers both our and the viewer’s responses and memories. It is another gift from Zucconi—his work lets you think.

A 2007 graduate of MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art), Zucconi is multi-everything: sculptor to photographer, computer engineer to musician. Like Thater, he has become a cornerstone artist in our collection.

Our original commission led to the acquisition of several other works: books, drawings, a photograph, a sculpture and more time-based media works. Digital works led to more traditional ones and then back to new media. The works are all conceptually based.

Untitled (Gamblin Radiant Blue), 2013, is a “sculptural painting.” It is a sphere of solid-cast natural rubber, weighing about 36 kilos, that was formed in a two-part compression mold. It has a dense presence that betrays any notion of lightness and bounce. The sphere’s rich color—a tint of ultramarine blue—almost hides the object’s imperfect, pock-marked surface and belies its humbleness. It is an unnatural, improbable object.

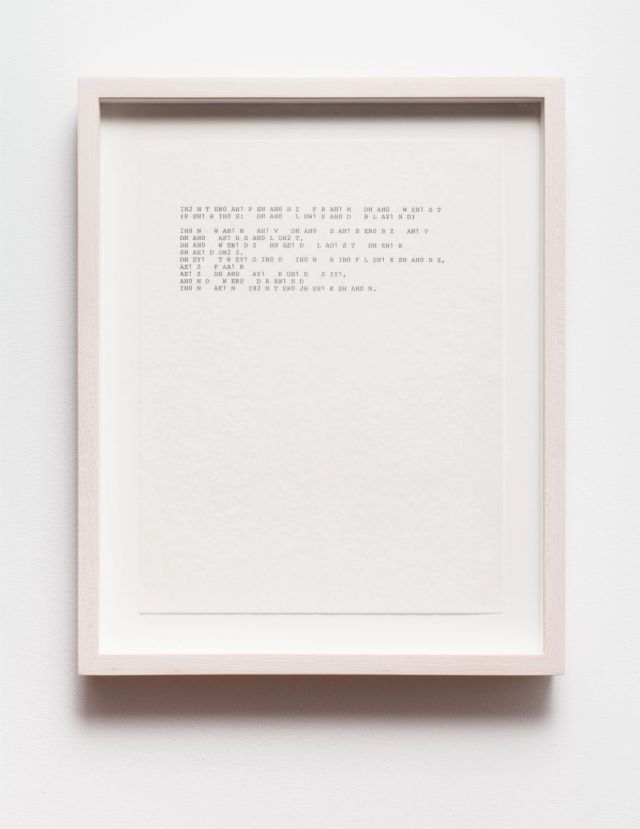

Two works from a series of typewriter “drawings,” nearly cryptograms, are rendered in typewriter ink on Eaton’s Corrasable Bond, a mid-1950s and 1960s erasable typing paper. The text is generated in ARPABET, a set of phonetic transcription codes developed in the 1970s, which were used in several early text-to-speech systems. Zucconi typed the transcription code, which is nearly readable phonetically. One of our two drawings is an ARPABET translation of Octavio Paz’s poem, INTERRUPTIONS FROM THE WEST (4) (Paris: The Lucid Blind). It reads:

In one of the suburbs of the absolute,

the words had lost their shadows.

They traded in reflections, as far

as the eye could see,

and were drowned

in an interjection.

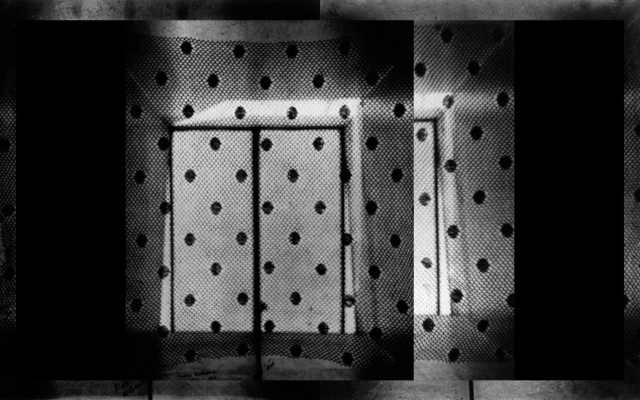

Our next Zucconi acquisition, Edge Transfer, a 2014 URL, was developed using Marcel Duchamp’s photographs of Draft Pistons (Piston de courant d’air), 1914. Two images continuously alternate left to right and right to left, shifting, passing, but never meeting. The work reaches directly into modern art history, linking specifically to the three irregular squares at the top of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

As for the images, Prahlad Bubbar Gallery suggests that “The exact meaning of the ‘Draft Piston’ photographs remain, like most of Duchamp’s practice, partly mysterious and veiled.” The gallery continues, Duchamp “claims to have created the photographs by using a square of dotted gauze and placing it in front of an actual window, with air currents blowing through. [He quipped,] ‘I wanted to register the changes in the surface of the square and use in my Glass the curves of the lines distorted by the wind. So I used gauze, which has natural straight lines. When at rest, the gauze was perfectly square—like a chessboard—and the lines perfectly straight—as in the case of graph paper. I took the pictures when the gauze was moving to the draught to obtain the required distortion of the mesh.’ (Duchamp, May 21, 1915).”

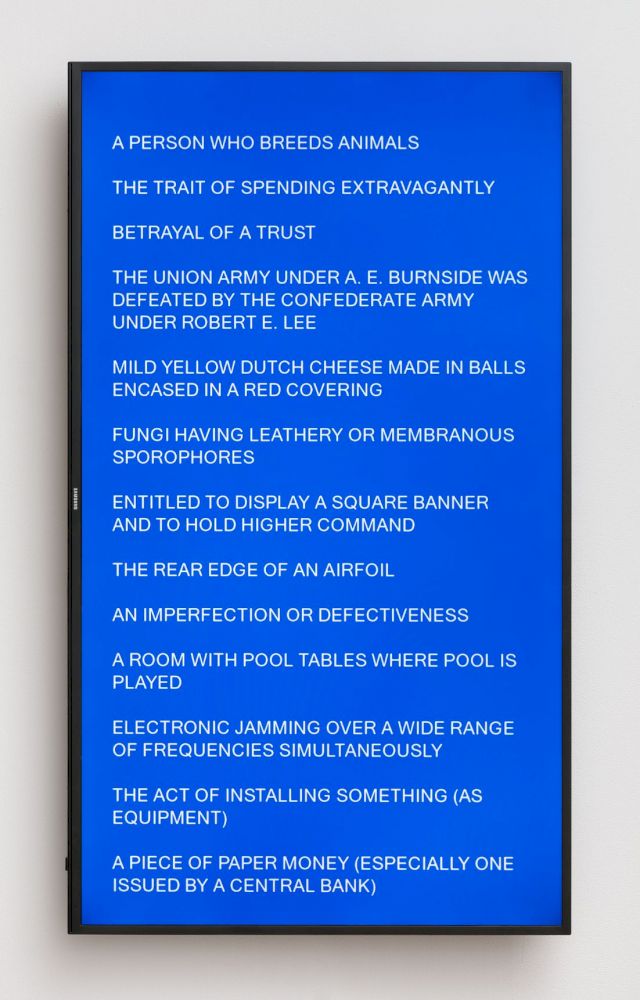

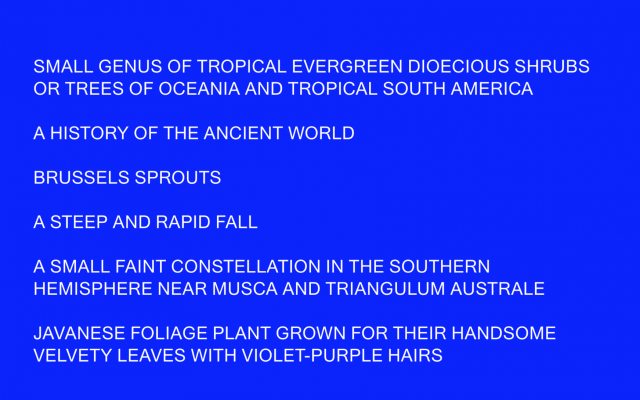

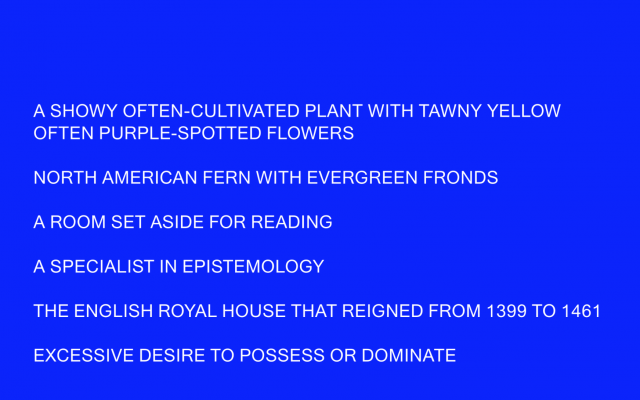

Our 2016 acquisition, dictionary.blue, is from a series of four URLs that present only the definitions of nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs via Internet-accessible English language dictionary databases and algorithms. While the piece is also a URL, Zucconi “framed” the work on (or in) a Samsung UHD 4K 55-inch flat-screen television. Embedded in the hardware is a Raspberry Pi microcomputer that processes the web application, offering definitions of nouns but not providing the words themselves.

Before arriving in Polly’s garden earlier this year, we acquired Colors, 2014. Again, Zucconi created a work that makes the viewer aware of how her or his mind processes and understands language and symbols. As the work unfolds like an endless sentence, the URL adds the name of one unique color after another in succession. But—and this is critical—the color’s name and hue color do not match. So, “mint green” can be peach, “white smoke“ can be turquoise and “floral white“ can be green.

We own other works on paper and nearly a dozen of Zucconi’s print-on-demand books, but his URLs have advanced our interest in art media innovation. The display of the URL pieces operates on any platform, underscoring the mobility of media. At one point earlier this spring, we had Zucconi’s Garden running on multiple screens in one of our offices. The synergy of Garden playing on four different devices, displaying different permutations from the millions of constructed images possible, resulted in visual pyrotechnics.

Digital technology has evolved to the point that it is seamlessly integrated into people’s daily lives. It has become a “plug and play” world. Access is democratic. It is art for now and art forever.